12-13 December, 1943: The Sinking of U-172

by Marc-André Haldimann

Foreword and Acknowledgements

U-172 has already been mentioned for the part she played during U-185's last patrol. She was one of the most successful U-boats of the 1942-1943 period and the story behind her sinking exemplifies the dire state of the U-Bootwaffe after the shocking defeat inflicted by the Allies from May 1943 onwards. The unusually long hunt which led to the demise of U-172 is covered by different sources, telling sometimes quite different stories; it seems thus necessary to present those sources and the way they were used by the author.

A German account was published in 1994 by Herbert Plottke; he served on U-172 as Bootsmannsmaat from her commissioning until her demise(1). Written in a non literary style, this 150-page document covers the events preceding the boat's last mission in detail; it is also valuable for providing an insight into everyday life on U-172 and the individuals who made up her crew. Unfortunately and probably unavoidably as it is basically a recollection written down some 40 years after the action, the chapter devoted to the hunt and the sinking is marred by redundancies and an imprecise time plot. Though an important part of the Report on the interrogation of survivors from U-172 and unnamed excerpts from the Action Report of USS Osmond Ingram are translated and sometimes commented on by Plottke, he did not use the Action Reports drafted by the pilots nor the other vessels involved. It is thus no surprise if his narration of U-172's demise shows significant discrepancies with the American Action Reports preserved in NARA.

The latter documents are without doubt the major source; though they might also contain some flaws, this author chose to follow the precise Action Reports description and timelines as most of them were drafted the very day reported events happened.

The Final Report of the U-172 crewmembers' interrogation is a third valuable source. Drafted 4 months after the sinking, it outlines the entire career of the boat, gives exhaustive details of her armaments and provides two versions of her sinking. Though very interesting, this document also must be approached with caution, as some of its contents are now thought to be hoaxes or false rumors intended to mislead the interrogators(2). The main account gives scant details of the hunt and the actual sinking, the length of the action probably being responsible for the lack of clear and unconfused records. The report given by an anonymous officer of U-172's staff and presented with a note of caution in the document is on the contrary a very coherent and precise narration, offering a valuable overview of the sinking (Final Report U-172 (1944), 83-88). As the details given by this last account fit well with the Action Reports and are often to be found in Plottke's recollections, it is the author's belief that it is the best German report on this action(3).

Thus the backbone for this research is provided by the NARA documentation and pictures(4); they are complemented whenever possible by the insights given by Plottke as to what was happening on U-172.

Once again, the author is deeply indebted to Jerry Mason for his excellent web site where these Reports are posted in extenso(5); he also most kindly provided the pictures from NARA used in this account. Axel Niestlé also kindly contributed his extensive knowledge of the German sources to track down the bias evident in Herbert Plottke's account and to provide important additional information. Frederic Haldimann again kindly investigated the weather conditions on the scene. Rainer Bruns provided valuable assistance in the choice of correct maritime terminology. Last but not least, Tonya Allen has to be thanked for her thorough reading, well founded critiques and helping hand with English syntax.

An Exceptionally Successful U-Boat

Commissioned on 5 November 1941, U-172 was a large Type IXC "Seekuh" U-boat built by the Deschimag-Bremen shipyard. Under the command of Kptlt Emmermann, U-172 undertook five patrols between 22 April, 1942 and 7 September, 1943; with the exception of the first, all were conducted in the mid and South Atlantic. Their results were impressive: no less than 27 ships for a total of 152.094 GRT were sunk, U-172 being the 17th top-scoring U-boat during the war(6). Those successes were achieved by a well-trained crew which remained largely unchanged throughout this time span. This policy was not standard for the Kriegsmarine, able and experienced crewmembers often being promoted and sent on training courses after only two or three patrols, but Kptlt. Karl Emmermann managed to keep his crew together until he himself was promoted at the end of the fifth patrol as Commander of the 6th U-boat Flotilla in Saint-Nazaire. The string of long-delayed crew promotions which then resulted brought to an abrupt end the closely knit team of U-172. No fewer than 25 new and inexperienced crewmembers, including the IWO, the IIWO and the LI, were ordered aboard to replace 18 seasoned men. The nomination as Commander of ObLt. z. S. Hermann Hoffmann, former IWO of the boat and thus well acquainted with her and the remaining crew, did serve to mitigate some of the disturbance caused by this massive change, but for Bootsmannsmaat Plottke, these were potentially lethal changes which compromised U-172's future(7).

A Difficult Beginning for the Sixth Patrol

After working out in their rest and training camp near Lorient the best possible integration plan for the green crewmen and officers, U-172's old hands had to cope with the drastically improved AA armament of the new Turmumbau IV conning tower installed during the dry dock refit. Plottke, responsible for AA defense, had to adjust from the older Turmumbau II type conning tower which held a 2 cm Flak/38 gun on each of the two platforms(8) and up to four 7.9mm MG 34 which could be temporarily set on the conning tower upper casing, to two double-barreled 2cm 38 M II guns on the enlarged upper platform and a Flakvierling, a quadruple barrel 2cm 38/43 U gun with shield, on the lower platform. These modifications were undertaken without prior notification of the AA crew who at that time were in Mimizan, near Bordeaux, for a one week practice course on older 2cm Flak/30 guns(9). These hasty and haphazard changes in crew and equipment were a contributing factor to the disaster which was to come.

The simple task of moving U-172 from dry dock to her berth in the U-boat pen was a challenge beyond the capabilities of the new IWO, who inadvertently rammed the pier with the U-boat's starboard bow. No damage was detected however, so U-172 left Lorient for her sixth patrol on 13 November, 1943 at 13.00. After emerging from their first deep test dive at 22.00 the same day, the crew noticed their boat was now trailing an oil slick; the mandatory stop at Saint Nazaire for loading the new T5 torpedoes, yet unavailable at Lorient, would be longer than planned as Oblt. z. S. Hoffmann was now compelled to carry out the necessary repairs.(10) This also provided the opportunity to relieve the obviously unfit new II WO; the replacement, Lt. z. S Wilhelm Reitz, was a more able young officer although also lacking any previous U-boat experience(11). In the dry dock, a leak in fuel bunker 7 was easily spotted, but the welding work lasted until 21 November. The badly welded steel plate repair was not accepted by Obermaschinist Walter Gerke; unfortunately for U-172, he was overruled by Alfred Löffler, the new LI, and the boat left France for Penang on 22 November at 14.00(12).

On the night of 3 December, the boat was attacked by a Leigh Light equipped plane, but evaded without damage. The next night, a faulty exhaust valve suddenly allowed fumes to enter the boat, leading to severe poisoning of the crew; it took a long time for the inexperienced mechanics to effect repairs. Though potentially disastrous, these incidents also had a positive side effect; they started to weld into one team the old and new crewmembers. On 10 December, after a mostly underwater, slow-speed voyage, U-172 emerged at 20.00 right next to her intended supply boat, U-219, which was already surrounded by four other boats. Under cover of darkness, she replenished provisions and refueled, leaving aboard U-219 the former LI, Oblt. Karl-Heinz Frohwein, who until then had been coaching the new LI. After Topping off his boat's supply, Oblt. z. S. Hoffmann, angered by U-219's constant radio traffic, gave orders to leave the meeting point on a southerly heading and to sail surfaced at high speed in an attempt to outrun the Allied search groups which he felt could not fail to be attracted by this steady radio stream(13). Oddly enough, U-219 ended up surviving all perils, being taken over by the Japanese Navy in July 1945 as I-505 and surrendered at Djakarta in August 1945(14), while U-172, driven by her trusted diesels dubbed Rackel and Dackel(15), was heading straight towards her destruction.

27 Hours to Destruction

On 12 December, U-172 was sailing at about 14 knots on a course of 090º southwest of the Azores. Weather was rather fine: a 10 knots east north east wind was stirring the surface of the Atlantic, while broken stratocumulus and scattered to broken cirrus clouds allowed a visibility of at least 5 miles. At 08.23, at the same moment as the watch crew on the conning tower became aware of an aircraft in the vicinity, the radioman, Erste Funkmaat Hans Hässler, picked up a radar contact(16). These alarms were triggered by Lt. (jg) E. C. Gaylord and his crew, radioman ArM1c W. E. Burke and gunner AOM3c J. P. Montgomery, flying in their VC-19 TBF-1c Avenger on a routine antisubmarine patrol, having taken off at 07.45 from the deck of escort carrier USS Bogue (CVE-9). Together with destroyers USS Clemson (DD 186), USS Du Pont (DD 152), USS Osmond Ingram (AVD-9) and USS George E. Badger (DD 196), the USS Bogue formed Task Group 21.13 which left Casablanca on 8 December with convoy GUS-23 and then parted to investigate the HF/DF'ed meeting point between U-219 and U-172(17).

U-172's crew went to battle stations at once, the AA gunner team manning their two twin 20mm and quadruple 20mm guns in a matter of seconds. Lt. (jg) Gaylord, who at 08.22 spotted the fully surfaced U-172 4 miles away, sent a contact report and swung his Avenger (plane code 13) towards the submarine. As he was racing in, he found that a broken hydraulic line prevented the bomb bay doors from opening. Cranking them open manually, at the same time he undertook violent maneuvers in order to bleed off excess airspeed for the attack, the hydraulic failure preventing the usual flaps and landing gear extension procedure.

The U-172 gun crew wasn't inactive as Gaylord's wildly yawing Avenger bore down on them. They managed to fire a full ammunition magazine from the Flakvierling, and short bursts from at least one of the two twin 2cm guns of the upper platform. Absorbed by the incoming plane and deafened by the roar of their weapons, Bootsmannsmaat Plottke and Obergefreiter Leutner, who manned the quadruple 2cm Flak guns on the lower platform, belatedly noticed the hissing of compressed air escaping through the opened valves of the diving tanks. Looking back at the conning tower, they realized with alarm that the watch crew and upper platform AA crew had already disappeared into the obviously crash diving boat. Running back to the conning tower, they managed to reopen the hatch and jumped into the boat, leaving Oblt. z. S. Hoffmann struggling to shut the hatch before the water reached it(18).

As these events unfolded, Gaylord noticed no defensive fire but did observe the slow reaction time of U-172: she started submerging at 08.24, when his plane was only two miles away. Selecting his acoustic torpedo (FIDO), he managed, thanks to the intensive troubleshooting he had undertaken, to drop his weapon 35 seconds after U-172 disappeared beneath the waves. He completed his pass by dropping a sonobuoy 800m ahead of the diving swirl. At 08.26:30, one minute after the FIDO entered the water, the Avenger crew saw a shock wave some 100m ahead of the diving swirl, and then a circular bubble pattern approximately 10 feet in diameter with a small column of spray in the center. The sonobuoy did not help to assess the result of Gaylord's attack as it did not start transmitting until 15 minutes after it contacted the water(19).

Inside U-172, no underwater explosion was noticed and no one realized how close their boat had come to being suddenly destroyed. After ordering the boat to be brought to a depth of 80m, Hoffmann elected to stay on silent running, while Plottke was treated for his injuries, his desperate jump into the control room from a height of 4.5m having left him with two broken ribs(20).

Meanwhile, Gaylord received help first from two FM-1 Wildcats (plane code 2 and 7) piloted respectively by Lt. (jg) J. R. Murray and Lt. (jg) C. E. Fetsch and, at 08.59, from another TBF-1c (plane code 16) flown by Lt. (jg) M. E. Burstad with radioman ArM1c M. O. Holland and gunner ArM1c J. W. Watwood(21). The Task Group Commander, Captain J.B. Dunn, also ordered the destroyers USS George E. Badger and USS Du Pont to race out towards the area. Burstad dropped a large pattern of sonobuoys on the scene which was easy to spot for the patrolling planes, thanks to an oil slick; as with the one dropped by Gaylord, they detected no submarine noises.

Aboard U-172, Hoffmann was under the false impression his boat had been attacked by a seaplane and, as time elapsed without further attack, thought his command was now out of danger. When informed that the hydrophones were picking up propeller noises, he thus ordered U-172 back to periscope depth, believing they were generated by a convoy sailing from the African coast. Unfortunately, since leaving St-Nazaire, U-172 had been plagued with trim and displacement problems and though the sea was moderate, the boat could not be held at depth. At 09.27, the conning tower broached some 400m ahead of the oil slick. Gripping the periscope, Oblt. z. S. Hoffmann saw nothing; fortunately for him and his crew, the circling planes were caught out of position and the boat disappeared again before any attack could be carried out(22). After steering towards the sound headings for a while, Hoffmann acknowledged that their constant changes of course were a bad omen; he thus ordered U-172 to go deep at 180m and to turn back on her initial 180º course. His second guess was better advised, those propeller noises being emitted by the converging destroyers, guided in by Lt. (jg) Fetsch aboard Wildcat number 7.

On the scene, at 10.52 the ships began an ASDIC search, USS Du Pont south of the oil patch, USS George E. Badger north of it. This first sweep was negative, no contact being raised either by ASDIC or by the sonobuoys. Continuing their sound detection search at 15 knots, USS Du Pont was the first to gain contact with U-172 and conducted a hedgehog attack at 12.14. USS George E. Badger also gained contact at 13.42 but did not attack until 14.48, dropping 5 depth charges(23). From then onwards, constant contact was maintained with U-172. By 19.14, twelve attack runs had been carried out by USS George E. Badger, ten followed by the release of between 5 and 8 D/Cs, for a total of 68 Mark VI depth charges dropped with settings between 50 and 200 meters(24).

Aboard U-172, tension grew as each D/C drop detonated closer to the boat, first bursting the upper deck torpedo containers and the depth gauges. A tendency of the bow to sink, necessitating constant displacement corrections, made LI Löffler surmise that there was also a fuel leak. This was evident on the surface, as the resulting oil patches were an excellent marker for the circling planes which transmitted their sightings and sonobuoy data to the destroyers, allowing them to perfect their attack runs. Obermaschinist Gerke's distrust for the hasty repair work carried out at Saint Nazaire was obviously well-founded: the badly welded steel plate on fuel bunker 7 had given way.

As the green crewmembers made a shocking first acquaintance with the terrifying blows wrought by D/Cs exploding in their vicinity, the old hands did their best to offset their damaging effects. They stemmed leaks, kept resetting blown fuses, and also kept a wary eye on the young crewmen, looking for any signs of breakdown. Meanwhile, Oblt. z. S. Hoffmann was ordering abrupt course changes according to the propeller noises, often backtracking in the disturbances left by the D/C detonations of the previous attack, but to no avail: USS Clemson and USS George E. Badger were closely tracking his command which, plagued by a host of leaks filling her bilge to a dangerous level, continued to descend with a 25º forward list. Only by ordering all the available men to the stern section, blowing Tank 5 and reversing both electric motors, could LI Löffler bring U-172 onto an even keel at a depth of 190m(25). The uninterrupted sonar pinging, the destroyers' high-pitched screws, the splashes of the D/Cs and the subsequent terrible beating went on and on. More severe leaks sprang in the forward torpedo compartment and in the electrical engines compartment with no possibility to use the bilge pumps at that depth; even worse, both magnetic and gyroscope compasses were smashed, depriving Hoffmann of any means of orientation(26).

Deception and Pursuit

After the last attack run at 19.14, neither destroyer was able to regain contact with U-172. Knowing that their prey could not make a fast underwater escape owing to the low battery level it must have by this time, USS Du Pont and USS George E. Badger, according to the Task Group Commander's instructions, set up an improvised box search plan which they executed from 19.48 onwards. USS Du Pont searched eastwards from the last contact and Badger westwards, both maintaining effective radar coverage of the scene. By stopping sonar investigation and navigating at moderate speeds, both ships hoped to accelerate the return of the U-boat to the surface by conveying the impression that they had departed the scene, and then catch her thanks to their radar coverage(27).

Aboard U-172, all could sense the end of the terrible beating: no more detonations, no more pinging, no high speed screws churning through the water. At 20.00, Oberfunkmaat Hässler heard the destroyers departing and could thereafter raise no more ship noises. Though the leaks were now all efficiently stopped, the situation aboard was critical: drained batteries, foul air, and the weight of the water in the bilge which made the boat barely controllable and then only by running both engines continuously in reverse. At 22.00, Oblt. z. S. Hoffmann gave the order to go to periscope depth; U-172 rose sluggishly and slowly, without detecting any hostile presence. Hoffmann and the IWO peered respectively into the attack and sky periscopes without seeing anything, while U-172 was making way backwards, still only controllable with reversed engines(28). This awkward situation lasted for an hour before the boat finally surfaced at 23.23, her air and electric supplies exhausted. The commander, a full watch party, and the complete AA crew climbed onto the conning tower; all guns were manned and loaded with ammunition. The sea was calm, visibility unrestricted and the moon full; while U-172 started to make way on the starboard diesel only, the port diesel having lost its lubricating oil, the lookouts noticed with dread a destroyer running on a parallel track, apparently some 2000m away on their starboard side. All the men on the conning tower wondered at the apparent lack of reaction from the American ship, hoping they were not seen(29).

This was not the case: USS George E. Badger immediately got a contact on its SF-1 radar set at 8'200 meters and soon established that U-172 was steering a course of 348º at 7 - 8 knots. Altering course accordingly and slowing to 12 knots in an effort to conceal his presence, Capt. Higgins tried to force the U-boat into the path of the moon. However, at 23.51 she seemed to stop and, fearing that she might dive, the decision was taken to engage her with gunfire at a range of 5'800 meters in the hope of inflicting additional damage. Three out of the four star shells fired did function but failed to light the target, while the U-boat proceeded again at her former speed and heading. USS George E. Badger tried to close in, but was constrained to restrict speed to 17 knots, the forward gun crew being unable to man their station at higher speeds. The bridge by then had a visual contact on U-172 but not the gun crews. The chase went on; a second try with two star shells yielded disappointing results(30). Meanwhile, aboard U-172, Hoffmann held fire; to prevent needless casualties, he ordered the AA team to go below decks where the remainder of the crew was working feverishly to carry out basic repairs. Plottke took over the steering of the boat, keeping her clear of the moon's path, while his commander tried to get in position to fire a torpedo from the aft tube. Without compasses or T.D.C., both tasks were arduous (31).

At a range of 3200 meters, Capt. Higgins engaged the U-boat with gun no. 1, using radar range. The pursuit reached its height at 00.18: the third round shot by USS George E. Badger fell close to U-172's starboard bow, seconds before Hoffmann ordered to fire from stern tube V and then to crash dive. The T.5 torpedo missed the destroyer whose crew did not see its track; only the typical sound signature heard on the ship's hydophone moved Capt. Higgins to order a zigzag course while closing in on the diving swirl, establishing a sonar contact soon afterwards. At 00.24, USS George E. Badger made her 13th attack run on U-172, dropping 5 more D/Cs. Sound contact was then lost until 01.12, USS Badger dropping her last 4 D/Cs at 01.15. Afterwards, a strong smell of diesel oil was perceived aboard and large patches of oil were seen on the moonlit sea(32).

The USS Du Pont, called in when radar contact was made 45 minutes before, arrived on the scene at 01.01. Both destroyers lost sound contact after the 01.15 attack and from 01.40 onwards resumed their box search tactics until 07.59; they were then ordered to rejoin USS Bogue.

The Final Plight

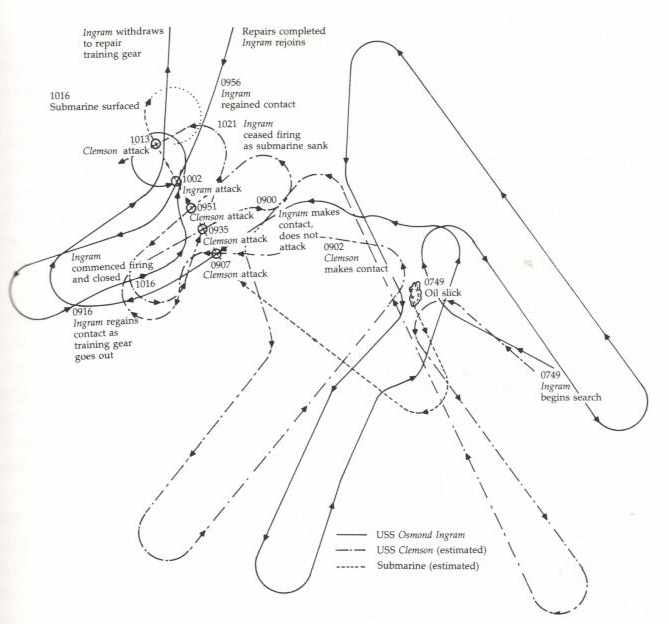

U-172 wasn't left alone for long after the destroyers' departure. At 08.10, Lt. (jg) Bradshaw and his crew on TBF-1c (plane code 20) sighted a moving oil slick on a 236º heading, some 7 miles from the previous attacks. USS Bogue and the remaining escorts were by then a mere 15 miles away; after USS George E. Badger and USS Clemson took up their screening position in the vicinity of USS Bogue, Captain Dunn ordered USS Osmond Ingram and USS Du Pont to investigate Lt. (jg) Bradshaw's finding. Dashing towards the scene at 24 knots, both destroyers arrived at 09.49 and started a retiring search pattern at 15 knots, some 900 meters apart. At 10.25, according to the latest plane radio report, they altered heading on a course of 180º true, thus matching closely U-172's desperate path. Sound contact was made at 11.02 by USS Clemson; she dropped her first depth charges at 11.08. Following in, USS Osmond Ingram obtained a good depth fix on the U-boat at 140 meters but did not attack owing to water disturbances from the previous depth charging. After regaining contact at 11.16, the destroyer had to abort attack when her sonar broke down. USS George E. Badger, her depth charges expended, took up station to guide USS Clemson who carried out her next attack at 11.35.

Aboard U-172, the situation was worsening at each new pounding: diving tanks on both sides were breached, continuous short circuits brought electrical systems down repeatedly, even the emergency lighting dying out for some time. Still worse, after another heavy depth charging, the shock waves activated two torpedoes in the bow tubes II and IV; the nerve-shattering screeching of their propellers petrified the crew until the hot torpedoes consumed their power supply and fell silent(33). Another bow torpedo, on the contrary, brought some relief: its compressed air reservoir was bled into the bow air bottles, thus bringing the available air pressure back to 80kg for a time(34). With low batteries and worsening air conditions, the crew kept quiet, trying to do what repairs were possible in an oppressive heat nearing 50º C. Thirst added to their plight, the drinking water tank having been breached some 10 hours earlier; to prevent dehydration, canned fruits were given out. The bow diving planes could only be moved by sheer force, and then only with grinding, revealing sounds, exhausting their operators who had to be replaced in quick succession. While the boat, getting heavier from the water accumulating in the bilge, was slowly sinking through 220m, ObLt. z. S. Hoffmann allowed the distribution of the beer bottles kept for celebrating the crossing of the Line. He was in no doubt about the state of his boat: with dwindling air supply, flooded negative buoyancy tanks adding another 10 tons of weight and both main pumps out of order, U-172 was about to plunge out of control toward the ocean floor. He thus ordered all officers, the boatswain and the coxswains to gather in the Control Room; after summing up their situation, he asked for their recommendation on whether to stay further down or try to reach the surface while the boat was not yet too heavy for their depleted compressed air reserve, now down to 47kg. All men present were unanimous: they wanted to take their chance on the surface(35).

Meanwhile, USS Clemson made a new attack at 11.51, followed at 12.02 by USS Osmond Ingram who dropped 9 more depth charges, and made the final D/C attack at 12.13. By then, U-172, tanks partially blown and pushed upwards by her electric motors draining what power was left in the batteries, was at 50m while her crew donned their Dräger Tauchrettern and their life jackets. All tanks were then blown and at 12.16, the bow of U-172 broke the surface at a steep angle some 200m off the starboard side of USS Clemson(36). According to Hoffmann's orders, the forward and galley hatches were opened as soon as the deck was above water, the conning tower being manned by Hoffmann with Watch I and II crews (Seemännische I und II). Gun one and two of USS Osmond Ingram opened fire immediately on the U-boat, the destroyer going to flank speed while closing on her target. Under a constant lashing of shells from Gun 1 and 20mm rounds from the secondary armament, U-172 picked up speed on her one working diesel, while making a sharp starboard turn in order to present her bow to the oncoming USS Osmond Ingram, intent on ramming. The first round of the destroyer's main armament hit the conning tower precisely where the gas bottle for the Aphrodite decoy balloons was stowed, starting a fire. Tightening her right turn and running at an estimated 8 knots, U-172 barely evaded USS Osmond Ingram's bow, while Hoffmann returned fire with an MG, supported by the two Semännische Unteroffiziere using their submachine guns(37). Their shooting killed one man outright and wounded another 8 (See Appendix B). The return fire was catastrophic: the hail of bullets raining from USS Osmond Ingram on U-172 (even Lewis .30 caliber machine guns were used) wreaked havoc among the men escaping through the forward and galley hatches.

The U-boat was also under constant air attack. As she surfaced at 12.16, the escort carrier USS Bogue was only 9 miles distant and two FM-1 Wildcats (code number 2 and 6), piloted respectively by Lt. (jg) M. E. Burstad and Ensign T. E. Jenkins, were circling the attacking destroyers together with a TBF-1c (code number 20) piloted by Lt. (jg) J. E. Ogle, with Radioman ARM2c A. G. White and Gunner ACM2c V. Aleresky. Ogle and Burstad both saw the bow of U-172 dart out of the water at an estimated 60º before leveling out on an even keel and starting her sharp starboard turn while the pilots observed "...men tumbling out of the conning tower and into the water." Ogle veered his Avenger and started a depth charge run from the port quarter; as he observed men abandoning U-172 he elected to make a strafing run instead. Both Burstad and Jenkins in their Wildcats then followed Ogle in and also strafed the crippled U-boat. All three planes then "swept back and forth across the U-boat, raking it with .50 caliber machine gun fire."(38) From their vantage point, Ogle, Burstad and Jenkins reported deck guns firing not only from USS Osmond Ingram, but from USS Clemson and USS George E. Badger as well.

For Herbert Plottke and his crewmates, those were terrible moments. While U-172 was running through her last starboard turn, ObLt. z. S. Hoffmann and 5 men from the first and second deck watch were crouching on the conning tower seeing others lying wounded or killed on the gun platforms and on the deck as they made their hasty exit, enlisted men first, followed by the coxswains and finally the officers. After all men had evacuated the boat except the six hiding in the battered conning tower and three in the Control Room, a drama unfolded in the Zentrale. Baltasar Schuy, the II Zentralmaat, a survivor from a German destroyer sunk in 1940 at Narvik, stubbornly refused to climb the ladder to the conning tower; he thus chose to remain entombed there as the LI Alfred Löffler ordered I Zentralmaat Arno Markgraf to open the diving tank vents(39). The last eight men then jumped into the ocean as U-172, still under way, sank on an even keel; her conning tower finally vanished at 12.21 at latitude 26º19' N and longitude 29º58' W, exactly 5 minutes after she broke surface for the last time. Since her first patrol, U-172 had been at sea for 398 days and sailed a total of 64'154 miles(40). Her descent to the bottom was punctuated by three underwater explosions, clearly heard at 12.24, 12.29 and 12.34 aboard USS Osmond Ingram(41).

According to Plottke's account, aircraft continued strafing survivors in the water for some time before they were left in peace by the departing planes(42); alas, their hope for a swift rescue was quickly dashed as the destroyers left the scene. Fortunately for Plottke and the seven other survivors from the conning tower crew, water and air temperature were a mild 22º C and posed no immediate threat to them. The 20 knot 068º wind was more of a problem: it generated an overlapping 2m short steep chop over 3m old swell and caused the men trying to keep together by forming a ring to drift apart. They struggled for the next two hours, while USS George E. Badger picked 23 men out of the water between 12.40 and 13.15, 15 others being taken aboard USS Clemson. Finally, their turn came as USS Osmond Ingram came alongside the swimming Germans, letting down nets on her flank. Thus were saved the last living crewmembers of U-172. Herbert Plottke became aware of a tense atmosphere as, after being wrapped in blankets and having their eyes cleansed of oil, they were led to the destroyer's bow compartment. It was forty years before Plottke was to learn the cause of this tension - unknown to them, they had just been retrieved by the very crew they had fired on after emerging for the last time(43).

The sinking of U-172 cost 13 men their lives, 10 more being injured (see Appendix A and B). The 46 survivors of U-172 could now look forward to 3 long years of POW life. For Herbert Plottke, this period ended on 14 December, 1946 with his arrival in Cuxhaven, exactly 3 years and one day after he escaped from the doomed U-172.

Notes

1. Plottke 1994.

2. Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944) A good example of bogus information is given on p. 76 : it is stated that an attempted crash dive failed owing to the captain's hat being wedged in the conning tower hatch, preventing it from closing properly.

3. The anonymous officer might be Oberleutnant Maximilian Coreth, the I WO; he was a member of a titled Austrian family. After being taken aboard USS Osmond Ingram, he was quickly separated from the other seven survivors and not seen again. The fact that Plottke's narration does fit with this account is of interest. As he had access to this document, one can surmise the details it contains fit well with Plottke's recollections, thus enhancing its likeliness.

4. For the NARA documents used, check the Sources. NARA files preserve 15 pictures from the sinking (80 G VC-19-5-395 to 397; 80 G VC-19-6-383 to 394); there are also duplicates and enlargements of this set, labeled 80 G 208198 to 208209. There is also a complete set of pictures recording a previous attack against U-172, on 7 April 1943, by two B 24D Liberators of 1st A/S Squadron, piloted by 1stLT W. E. Thorn and 1stLT Easterling; they are numbered 80 G 2854-273 to 2854-282 with enlargements 285H to 285N. Information by courtesy of Jerry Mason.

5. Jerry Mason's fundamental site publishes the primary sources including some of the pictures available on U-172, preserved by the National Archives at College Park, Maryland. They are available at this URL: http://www.uboatarchive.net/U172.html

6. Plottke 1994. It is corrected according to U-172's page on Uboat.net at the following address: http://uboat.net/boats/u172.htm.

7. Plottke 1994, 89-90.

8. Information courtesy of Axel Niestlé; Plottke, 51, mentions only briefly that U-172 had already two 2cm guns to fend off attackers.

9. Plottke 1994, 91. This assertion is contested by Axel Niestlé; in his opinion, it is highly improbable that a gunnery course would have been carried out as late as October 1943 with antiquated 2 cm Flak/30 guns, as the Flak Vierling had been a standard fitting since August 1943.

10 Information by courtesy of Axel Niestlé; Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944), 74, mentions the loading of two "new type" torpedoes in Saint-Nazaire, but without further explanation.

11 Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944), 75.

12. Plottke 1994, 96-97; Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944), 75.

13. Plottke 1994, 98-99.

14. For a complete career summary of U-219, see the following URL: http://uboat.net/boats/u219.htm

15. Brennecke (2000), 74.

16. Plottke 1994, 99; Gaylord E. C. (12.12.1943), 2.

17. Y'Blood 1983, 120; Higgins, E. M (12.17.1943), 1.

18. According to Plottke, U-172's crew engaged "...two carrier borne aircraft." (Plottke 1994, 99). The sighting of two planes is supported neither by Lt. (jg) Gaylord's attack report (Gaylord E. C. (12.12. 1943), 2) nor by the Interrogation Report of Survivors (Final Report U-172 (04.07. 1944), 78); the watch crew spotted a lone plane, some of the crew thinking they heard a second plane in the clouds (Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944), 79-80). According to Plottke, the aircraft were driven back and disappeared in the clouds, then dropped a Mark 24 Mine and a sonobuoy (Plottke 1994, 99).

19. Y'Blood 1983, 120.

20. Neither Plottke's account nor a survivor's statement mention an underwater explosion.

21. Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944), 2.

22. Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944), 79.

23. Higgins, E. M (12.17.1943), 1.

24. Higgins, E. M (12.17.1943), 2. The report gives the following summary :

| Run No. | GCT | No. of Charges Mean Depth Setting | Fathometer Reading | Range at Loss of Contact |

| 1. | 1448 | 5 - 550' | None | 500 yards. |

| 2. | 1527 | 7 - 550' | 92 F | 600 yards. |

| 3. | 1601 | 8 - 375' | None | 150 yards. |

| 4. | 1641 | 8 - 225' | 100 F | 800 yards. |

| 5. | 1655 | 8 - 425' | 105 F | 750 yards. |

| 6. | 1713 | 8 - 475' | None | 650 yards. |

| 7.# | 1729 | None | None | 400 yards. |

| 8. | 1749 | 8 - 275' | None | 550 yards. |

| 9. | 1821 | 6 - 475' | 90 F | 550 yards. |

| 10.# | 1835 | None - 500' | None | 125 yards. |

| 11. | 1853 | 5 - 225' | None | 250 yards. |

| 12. | 1914 | 5 - 375' | None | 600 yards. |

| 13. | 0024 | 5 - 125' | None | ? yards. |

| 14. | 0115 | 4 - 175' | None | 450 yards. |

| # Did not fire. |

26. Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944), 85.

27. Higgins, E. M (12.17.1943), 1-2.

28. Plottke 1994, 101-102.

29. Plottke 1994, 102 Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944), 82.

30. Higgins, E. M (12.17.1943), 2.

31. Plottke 1994, 102; Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944), 85.

32. Higgins, E. M (12.17.1943), 2.

33. Plottke 1994, 103; Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944), 87.

34. Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944), 87.

35. Plottke 1994, 104-105; Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944), 88.

36. Ogle, J. E. (12.13. 1943), narrative of attack.

37. Plottke 1994, 106; Miller, R. F. (12.20.1943), 2.

38. Ogle, J. E. (12.13. 1943), narrative of attack.

39. Plottke 1994, 108.

40. Plottke 1994, 106.

41. Miller, R. F. (12.20.1943), 2.

42. Picture VC-19-6-392 shows no trace of machine gun fire at the sinking boat, nor does picture VC-19-6-394 show bullet splashes near the swimming survivors.

43. Plottke 1994, 107-108.

Sources:

Brennecke, J. (2000), Jäger Gejagte. Deutsche U-Boote 1939 - 1945, Koehler, 8th edition, p. 74.Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944) : Final Report - G/Serial 29. Report on the interrogation of survivors from U-172 sunk 13 December 1943, NARA, College Park, Maryland. Published on http://www.uboatarchive.net/U-172INT.htm, by J. Mason.

Gaylord, E. C. (12.12.1943) : Report of antisubmarine action by aircraft, no. 5. NARA, College Park, Maryland. Published on http://www.uboatarchive.net/U-172ASW6-5.htm , by J. Mason.

Higgins, E. M (12.17.1943), USS George E. Badger (DD196). Report of sinking of Enemy Submarine, NARA, College Park, Maryland. Published on http://www.uboatarchive.net/U-172BadgerSinkingReport.htm by J. Mason.

Miller, R. F. (12.20.1943), USS Osmond Ingram (AVD9). Action Report. NARA, College Park, Maryland. Published on http://www.uboatarchive.net/U-172OsmondIngramRPT.htm , by J. Mason.

Ogle, J. E. (12.13. 1943) : Report of antisubmarine action by aircraft, no. 6. NARA, College Park, Maryland. Published on http://www.uboatarchive.net/U-172ASW6-6.htm , by J. Mason.

Plottke, Herbert (1994), Fächer loos ! U-172 im Einsatz. In den Weltmeeren von Rio bis Kapstadt. Ein Tatsachenbericht aus den Jahren 1942 - 1943, Podzun - Pallas Verlag.

Uboat.net (2001): Gudmundur Helgason's site gives all the essential background data available on U-172 (http://uboat.net/boats/u172.htm)as well as a biographical sketch of ObLt. z. S. Hoffmann (http://www.uboat.net/men/commanders/h.htm ).

Uboatarchive.net (2000) Jerry Mason's site publishes all the primary sources about U-172's sinking. His work greatly eases access to the existing references: http://www.uboatarchive.net/.

Y'Blood, W. T. (1983), Hunter-Killer. U.S. escort carriers in the battle of the Atlantic, Naval Institute Press, Maryland.

Marc-André Haldimann

Appendix A: The crew of U-172 as listed in Final Report U-172 (04.07.1944), Annex; completed by Plottke (1994), 94 - 96.

Name - Rank - USN Equivalent - Age

Hoffmann, Hermann

Oberleutnant z. S.

Lieutenant (j.g.)

22

Coreth, Maximilian

Oberleutnant z. S.

Lieutenant (j.g.)

24

Heitz, Friedrich Wilhelm

Leutnant z. S.

Ensign 23

23

Löffler, Alfred

Leutnant (Ing.)

Ensign (Engineering)

25

+Vole Gerhard

Oberassistenzarzt

31

Schröter Karl

P.K. und Artilleriemaat

Press Correspondent and Gunner's Mate

31

Duwe, Karl

Obersteuermann

Quartermaster of Warrant Rank

24

Schmidt, Erich

Oberbootsmaat

Boatswain's Mate 2cl

25

Plottke, Herbert

Bootsmannsmaat

Coxswain

23

+ Padeike Walter

Bootsmannsmaat

Coxswain

21

Gerke, Walter

Obermaschinist

Machinist

30

Schubert, Max

Obermaschinist

Machinist

29

Holzke, Heinz

Maschinenobermaat

Machinist'sM. 2cl

23

Lemke, Otto

Maschinenobermaat

Machinist'sM. 2cl

24

Markgraf, Arno

Maschinenobermaat

Machinist'sM. 2cl

26

Banse, Ewald

Maschinenmaat

Fireman 1cl

23

Hoffmann, Walter

Maschinenmaat

Fireman 1cl

26

Peter, Alfred

Maschinenmaat

Fireman 1cl

23

+ Schuy, Balthasar

Maschinenmaat

Fireman 1cl

25

Hässler, Hans

Oberfunkmaat

Radioman 2cl

24

Birnstiel, Werner

Funkmaat

Radioman3cl.

21

Schneck, Karl

Mechanikermaat

Torpedoman's Mate 3cl

20

Christiani, Heinz

Matrosenobergefreiter

Seaman 1cl

21

Hülsmann, Ernst

Matrosenobergefreiter

Seaman 1cl

18

Krüger, Bernhard

Matrosenobergefreiter

Seaman 1cl

21

Leuthner, Willi

Matrosenobergefreiter

Seaman 1cl

22

Missfeldt, Erdmann

Matrosenobergefreiter

Seaman 1cl

21

Rose, Gerhard

Matrosenobergefreiter

Seaman 1cl

21

Sager, Hermann

Matrosenobergefreiter

Seaman 1cl

21

+ Schäfer, Helmut

Matrosenobergefreiter

Seaman 1cl

21

+ Schmidt, Alfred

Matrosenobergefreiter

Seaman 1cl

20

Wieser, Josef

Matrosenobergefreiter

Seaman 1cl

21

Höhmann, Horst

Matrosengefreiter

Seaman 2cl

19

+ Look, Ernst

Matrosengefreiter

Seaman 2cl

20

Schulze, Alfred

Matrosengefreiter

Seaman 2cl

19

Bender, Rudi

Matrose

Apprentice Seaman

20

Brandner, Wilhelm

Matrose

Apprentice Seaman

20

Braunagel, Helmut

Matrose

Apprentice Seaman

21

Heiden, Otto

Matrose

Apprentice Seaman

19

+ Waltl, Werner

Matrose

Apprentice Seaman

19

Bierwolf, Hans

Maschinenobergefreiter

Fireman 2cl

19

Dürr, Peter

Maschinenobergefreiter

Fireman 2cl

20

Heil, Kurt

Maschinenobergefreiter

Fireman 2cl

20

Köhler, Anton

Maschinenobergefreiter

Fireman 2cl

20

Lindmoser, Karl

Maschinenobergefreiter

Fireman 2cl

22

+ Madrowsky, Willy

Maschinenobergefreiter

Fireman 2cl

22

+ Stenzel, Walter

Maschinenobergefreiter

Fireman 2cl

22

Bunda, Karl

Maschinengefreiter

Fireman 3cl

19

Burger, Heinrich

Maschinengefreiter

Fireman 3cl

19

+ Fuhrmann, Horst

Maschinengefreiter

Fireman 3cl

19

Gutzeit, Günther

Maschinengefreiter

Fireman 3cl

19

Kutsch, Walter

Maschinengefreiter

Fireman 3cl

19

Peter, Ernst

Maschinengefreiter

Fireman 3cl

19

Kühn, Isidor

Funkgefreiter

Seaman 2cl

20

+ Liebschner, Egon

Funkgefreiter

Seaman 2cl

21

Meissner, Günther

Mechanikerobergefreiter

Seaman 1cl

21

Bender, Egon

Mechanikergefreiter

Seaman 2cl

18

Bierfreund, Martin

Mechanikergefreiter

Seaman 2cl

19

+ Feind, Ewald

Mechanikergefreiter (A)

Seaman 2cl

20

+ Denotes casualty.

Appendix B: Casualties aboard USS Osmond Ingram (AVD 9) according to Miller, R. F. (12.20.1943), 2.

Name - ID - Rank

+ Crowell, Rex Dolos

621 89 221

F1c

Penoyer, Charles Clinton

620 27 30

MM2c

Brody, Paul

298 91 54

CMM

Rockwell, Harry William

602 23 21

F1c

Murnan, Paul Andrew

710 91 56

F3c

Ward, Thomas William

68 88 07

SF2c

Sayers, Lee Monger

725 30 80

MM2c

Owen, Chester Lee

630 06 01

F1c

Craig, Robert Wilder

658 91 71

S1c

This article was published on 4 Jul 2001.

|

Books dealing with this subject include

|