Sinking of the CSS Hunley

by Robert Derencin

Introduction

The American Civil War lasted from 14 April 1861 to 26 April 1865. The Union States consisted of 22 states and the Confederacy consisted of 11 states. The War was for the most part fought on land. In spite of it, the naval war was also significant for the final result of the Civil War. On 17 April 1861 the Confederacy approved piracy. Two days later, on 19 April 1861 the Union declared blockade of the Confederacy. The naval war was managed in coastal areas, on rivers and against maritime traffic of the enemy, by means of blockade and by cruising war. It was war without real naval battles. The Confederacy managed the cruising war excellently, but without real effect on the final result of the Civil War. The Unites (Northern) States had domination in ships and other war material and their blockade of the Confederacy, i.e. the Southern coast had much more effect on the final result of the Civil War.

One of the most important Southern ports was Charleston. Charleston was under blockade from 5 April 1863 to 17 February 1865, when the town capitulated. In front of Charleston was strong task force of the Union Navy (USN). A few individuals from the Confederacy side, the best known of them Horace L Hunley, invented and built the first successful submarine in the world, the CSS Hunley.

On 17 February 1864 the CSS Hunley attacked and sank the USS Huasatonic. After that the CSS Hunley herself sank. The reason for the sinking of the CSS Hunley is unknown. In this article will be get some possible scenarios of that what might have happened to the CSS Hunley during that historic night.

Technical description of the CSS "Hunley"

The CSS Hunley was made from a cylindrical iron steam boiler. The boiler was deepened and lengthened. Each end of the submarine was tapered. On the top of the submarine's hull were two conning towers, near the submarine's ends. The forward conning tower was intended for the submarine's captain and the aft conning tower was intended for the submarine's first officer. On the both conning towers there were positioned several small viewing ports (portholes). The conning towers were also intended for passing the crew in and out of the submarine. On the top of the submarine's hull (between the conning towers) was also positioned snorkel box. The snorkel box was intended to enable fresh air supply when the submarine was submerged. The snorkel box consisted of four-foot movable snorkel tubes. The snorkel tubes were fitted with stopcocks. The stopcocks made impossible penetration of water into the submarine when the submarine was submerged below four feet. Additional iron weights were bolted on the underside of the submarine's hull. If the submarine needed additional buoyancy, in an emergency situation, the crew was able to take off the iron weights by unscrewing the heads of the bolts, from inside of the submarine. In that case the submarine could rise to the surface more easily.

CSS Hunley was manually powered. The crew (eight men) turned a crankshaft, which was connected to the submarine's propeller. Hunley's maximum speed, when the crew was working their best, was about 3 knots.

There were two ballast tanks inside the submarine. The ballast tanks were positioned near the end of the submarine; i.e. there were forward ballast tank and aft ballast tank. Both tanks were opened on their tops. Each tank was equipped with a cock (valve) and with a hand pump and could be flooded with water by opening its valve (cock). Also it was possible to eject the water from the tank by means of its hand pump. When the submarine captain ordered submerging, the tanks were flooded. When the captain ordered surfacing, the tanks were pumped dry.

The submarine had two dive planes, positioned on each side of the submarine, closer to the submarine bow. A horizontal rod connected the dive planes. By moving a lever inside the submarine it was possible to adjust position of the dive planes and on that way it was possible to change the submarine's underwater position and depth.

The CSS Hunley had a bow-mounted spar torpedo. The plan was to ram the torpedo into the hull of an enemy ship. Because of more easily ramming, at the end of the torpedo was a barb. After the ramming, the submarine would reverse its course, back away and the torpedo would be detached from the spar (i.e. from the submarine). After the submarine reached a safe distance from the enemy ship (and from the torpedo) the torpedo would be detonated by a line that was connected between the torpedo and the submarine.

Near the forward ballast tank (the submarine's captain working place) were located a steering wheel, compass, depth gauge (mercury gauge, used to show depth of the submarine) and a candle. The candle was used to ensure light in the submarine's cabin. Also, the candle indicated condition of air supply.

The submarine's crew and test drives

CSS Hunley was designed for a crew of nine men. Position of the submarines captain was near the submarines forward tank. The Captain was the commander. He was observing situation around the submarine through the forward conning tower, navigating, steering the submarine, handling with the forward ballast tank (sea cock and hand pump). The Captain handled the dive planes (by the lever inside of the submarine). The submarine's First Officer was second in command. His position was near the aft ballast tank. Like the Captain, the First Officer was observing situation around the submarine through the aft conning tower. Also, the First Officer was handling with the aft ballast tank (sea cock and hand pump). When necessary the First Officer helped the submarine crew to turn the hand-cranked propeller. There were also seven men intended to turn the hand-cranked propeller.

Because of all mentioned above, it is clear that position of the submarine's Captain was vital. Not just because the Captain was responsible for commanding but also because the Captain was handling many devices and instruments (compass, dive planes' lever, forward sea cock and hand pump, steering wheel, candle, and mercury gauge). There were many test drives done by the CSS Hunley. But, during two test drives the submarine sank, both times because of personal (the Captains') errors.

The first sinking of the CSS Hunley happened on 29 August 1863, during a test drive in Charleston harbor. The crew consisted of nine members of the CS Navy. The submarine commander was the CS Navy Lieutenant Payne. When the submarine was still surfaced, and the submarine's hatches (manholes) were still opened, Lieutenant Payne ordered "go ahead". Then, Lieutenant Payne "got fouled in the (forward) manhole by the hawser and in trying to clear himself got his foot on the lever which controlled the fins (i.e. dive planes)". The fins (dive planes) were pressed down and the CSS Hunley began to dive. Because the hatches (manholes) were still opened the submarine was rapidly filled with water. Four crewmembers succeeded to leave the submarine through the manholes (including Lieutenant Payne). Five crewmembers died.

The CSS Hunley sank because of Lieutenant Payne's personal error. The CS Army and Navy commanders believed that members of the CS Navy were more capable to navigate with the CSS Hunley than "amateurs". But they forgot that the CSS Hunley was something completely new in naval warfare, invented and built by the same amateurs. The CS Army and Navy commanders were thus partly responsible for the tragedy.

After the first sinking of the CSS Hunley, the CS Army and Navy commanders realized that the Hunley's crew must be more familiar with construction and working operations of the submarine. Because of that, Horace L. Hunley went to Mobile, in the place where the submarine was constructed and built, the Parks and Lyons machine shop, to recruit the new crew. For the new submarine's commander was appointed the CS Army Lieutenant George E. Dixon, a young but experienced and brave soldier.

On 15 October 1863 the CSS Hunley sank for the second time. That day Lieutenant Dixon was out of Charleston and Horace L. Hunley stepped in as the commander. The crew consisted of eight men, including Horace L. Hunley. In the first moments of test driving the submarine navigated surfaced, with the empty ballast tanks. The submarine cabin was lighted through the portholes (i.e. by daylight, which passed through the portholes positioned on the both conning towers). Then, Captain Hunley decided to submerge the submarine. He partly turned down the dive planes and then opened the forward ballast tank's cock (because the submarine needed additional ballast). The submarine submerged and in that moment the cabin was in total darkness. Because of that Captain Hunley wanted to light the candle, to ensure light in the cabin. And, he forgot to close the forward ballast tank's cock (valve). The forward ballast tank was soon flooded by water and the water continued to flood the entire submarine's cabin. The submarine became overflowed and sank very fast. The crew tried to eject the water from the submarine.

After recovery of the submarine the aft cock was found properly closed and the aft ballast tank was nearly empty. The cock of the forward ballast tank was wide open, and the cock wrench not on the plug but lying on the bottom of the submarine. Captain Hunley unsuccessfully tried to eject the water by using the forward hand pump.

The crew tried to release the iron keel ballast but didn't turn the keys quite far enough. Because of that the iron keel ballast remained attached to the submarine. After the recovery it was found that the bolts that held the iron keel ballast had been partly turned, but not enough to release it. The entire crew of 8 men died.

The sinking happened as a result of Captain Hunley's personal mistake. Captain Hunley wasn't the submarine commander. But, in absence of Lieutenant Dixon, he took his position and made the fatal mistake. Nonetheless after the recovery of the submarine, Lieutenant Dixon and others named the submarine "Horace L Hunley" to honor Captain Hunley's merits. Even more, after the recovery Lieutenant Dixon spoke with the CS Navy First Engineer J. H. Tomb and told him that the sinking happen because the crew forgot to close the "after valve". Possible he wanted to protect Captain Hunley.

After the second sinking the CSS Hunley was recovered and restored. Lieutenant Dixon convinced authorities that it would be possible to navigate and make a successful attack with the submarine. He recruited a new crew (the CSS Hunley's third crew) and made many test drives with the submarine. Because of previous experiences Lieutenant Dixon made some changes in his strategy.

According to the CS Navy First Engineer J. H. Tomb Lieutenant Dixon's original intention was to submerge the submarine and strike from below. But in that case the torpedo would be above the submarine and the submarine could be sunk because of two reasons. The first reason could be explosion of the torpedo. If the submarine would not be damaged because of the explosion, the submarine had to be submerged, at the angle of (about) 45 degrees (bow up, stern down). It was very hard to keep that position with the CSS Hunley's navigational capacities and it was almost impossible to get reversed course with such positioned submarine. Because of reasons mentioned above the submarine was probably surfaced during the attack on the USS Huasatonic.

The mission

Lieutenant Dixon arranged with Lieutenant Colonel Dantzler (from Battery Marshal) that he would show two blue light signals when the submarine was ready for return to base after attack. The submarine went to attack an enemy ship on 17 February 1864. Weather conditions were: clear, the night bright and moonlight, moderate wind from the Northward and Westward, sea smooth and tide half ebb. The attack took place between approximately 8:45 PM and 9:00 PM. The submarine was observed for the first time at about 8:45 PM, 75 to 100 yards from the USS Huasatonic, by Acting Master John Crosby, who was the Officer of the Deck of the USS Huasatonic. The unknown object observed in the water was looking to him something like a porpoise, but when he noticed that the unknown object started to move towards the USS Huasatonic very fast, he gave alarm. Lieutenant F. J. Higginson, the USS Huasatonic Executive Officer, arrived on the deck immediately. He asked what was going and then he noticed: "Something resembling a plank moving towards the ship at a rate of 3 to 4 knots. It then stopped and appeared to move off slowly".

Naturally, after the CSS Hunley struck the torpedo into the USS Huasatonic the submarine reversed its course to reach safe distance and detonate the torpedo. According to Lieutenant Higginson the torpedo struck the ship forward of the mizzenmast, on the starboard side, in a line with the magazine. The torpedo exploded about three minutes after the submarine was observed in the water for the first time.

CSS Hunley: An attack by a semi-submerged submarine

At least few men on board of the USS Huasatonic opened fire from small arms on the submarine: Among them were Captain Charles W. Pickering (Commanding Officer), Lieutenant Higginson (Executive Officer), Acting Master John Crosby (Officer of the Deck) and Ensign Charles Craven. By the witnesses the submarine "exhibited two protuberances above and made a slight ripple in the water". The protuberances were the submarine's conning towers and the submarine made the slight ripple because the submarine was surfaced during the attack. Around 9:30 PM the blue light signal was observed and answered from the Battery Marshal. The signal was interpreted as a request from the submarine for a light to guide them safely back into port.

Seaman Robert Flemming (from USS Canandaigua) also observed the signal. USN Captain Green, who was Commanding Officer of the USS Canandaigua, was informed at about 9:20 PM about the attack. Crewmembers of the USS Huasatonic reached the USS Canandaigua in one lifeboat and then informed him about the attack. They told that the attack was made by "rebel torpedo craft". The USS Canandaigua reached to the place of the sinking of the USS Huasatonic at 9:35 PM.

The USS Huasatonic sank. Two officers and three men perished but the rest of her crew was rescued.

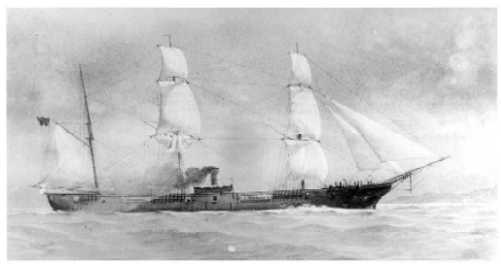

The sloop USS Huasatonic. A screw sloop of war built in 1861 she was 207 feet long and carried a crew of 160.

CSS Hunley never returned to base. The submarine sank with all its crewmembers. It is not known for sure why the submarine sank. In the next chapter will be tried to explain some possibilities what happened to the submarine after the attack.

Possible scenarios

There have been many theories as to why the CSS Hunley sank. According to the theories the CSS Hunley sank because of result of the torpedo explosion, or because of sinking of the USS Huasatonic, or as a result of the USS Huasatonic's defending gunfire (by light weapons). The last theory is that the submarine sank because of worsening weather conditions. The CSS Hunley did not sink because of aforementioned theories. After the attack (after the USS Huasatonic's defending gunfire, after the torpedo explosion and after the USS Huasatonic sank) the blue signal was sent from the submarine. That means that Lieutenant Dixon believed that the submarine and its crew would be able return to base safely. Neither the crewmembers were so injured nor the submarine so heavily damaged as to make return to base impossible.

Changing weather conditions - A few hours after the attack weather conditions were getting worse. That could be a possible reason why the submarine sank. The crew was exhausted (physically and psychically) and in such conditions everything is possible. But since that happened hours after the attack and after the blue light signal was sent this possibility is not likely.

Lieutenant Dixon ordered the blue light signal to be sent because he was sure that the submarine was ready for safe return to base. Also, Lieutenant Dixon was a brave and experienced soldier (he was member of the CS Army) and he knew that the most dangerous part of any military action was not coming to place of an attack and the attack itself but the return to base. Also, Lieutenant Dixon knew about the personal errors of the previous submarine commanders (Payne and Hunley) and it's unlikely that he made make the same mistakes.

The USS Canandaigua came to the place of the sinking of the USS Huasatonic very soon. The arrival of the USS Canandaigua was observed from the CSS Hunley. Because of that Lieutenant Dixon possibly decided to navigate submerged, completely submerged or at snorkel depth. If he decided to navigate at snorkel depth (up to four feet) he would turn the snorkel in such position to ensure flow of fresh air into the submarine. The snorkel tubes were equipped with the stopcocks. In case that the submarine submerged to depth below four feet, the stopcocks enabled water to get inside the submarine. There was possibility that the stopcocks were damaged during the torpedo explosion or for another reason, the submarine submerged below four feet and the water overflowed the submarine cabin.

Perhaps Lieutenant Dixon decided to navigate completely submerged, on the depth below four feet. Then both tanks were flooded and Lieutenant Dixon turned the lever of the dive planes to down position (for diving). Because of the explosion and because of the sinking of the USS Huasatonic around the submarine were floated many pieces of wood, ropes and other things from the USS Huasatonic. Perhaps one peace (or even few pieces) of the things mentioned above got to vicinity of the submarine. In that case it was quite possible that the piece of wood or rope came between the submarine hull and the dive plane(s).

At the moment when the Lieutenant Dixon turned the lever in down position, the piece of wood or rope could remain blocked in the place between the submarine hull and the dive plane(s). If that was the case the dive planes could not be returned either to their horizontal position (to retain reached depth) or in an upward position (for surfacing). It is possible that Lieutenant Dixon turned down the dive planes lever, the submarine became to submerge and when he wanted to turn the lever in horizontal position he was not able to do that. It was impossible to release the dive planes from inside the submarine, and the submarine submerged deeper and deeper, down to the bottom. There is one additional possibility; perhaps the submarines propeller was also blocked by the piece of wood or rope.

When the submarine came to the sea bottom both ballast tanks were flooded with the water, but the tanks and the submarine cabin weren't overflowed. It is quite possibly that the crew tried to empty the ballast tanks but sand and mud around the submarine could have made that impossible. Also it is quite possible that the crew tried to release the iron keel ballast but for some reason they were unable to do that. The report of the wreck of the USS Huasatonic (made by USN, on 27 November 1864) "the wreck settled in the sand about five feet, forming a bank of mud and sand around her bed. The sea bottom in area of 500 yards around the wreck was dragged. The torpedo boat (i.e. the Hunley) wasn't found." Although wreck of the CSS Hunley wasn't in the vicinity of the wreck of the USS Huasatonic it is quite possible that the submarine wreck did settle in similar conditions, i.e. in the mud and sand.

Conclusion

CSS Hunley was the first successful submarine in naval history. Hunley's construction, equipment and navigational characteristics perhaps were not perfect but she was nonetheless at the top of the technology at the time and there is no doubt that the CSS Hunley was a real submarine. It was the first time that a submarine successfully attacked an enemy ship. This was also the first time that a submarine sank under the mysterious circumstances, but not the last. From the times of the CSS Hunley to these days many submarines have sunk under mysterious circumstances. It is not uncommon that submarines sink (or rather disappear) under mysterious circumstances. After all, all about submarines (technology, tactics, etc) are mysterious.

The CSS Hunley did its role completely and perfectly. The USN Rear-Admiral Dahlgren, Commanding Officer of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron in his report (on 7 January 1864) wrote that the "rebels" (i.e. the CS Army and Navy) had three submarines. USN Rear-Admiral Dahlgren also knew of accidents during test drives (trials). In the report he also described submarine tactics. The informers were Confederacy deserters that escaped from the besieged Charleston.

Two days after the attack, on 19 February 1864, USN Rear-Admiral Dahlgren wrote: "The whole line of blockade will be infested with these cheap, convenient and formidable defenses, and we must guard every point. The measures for prevention may not be so obvious." Two facts are evidently from above mentioned report (dated 19 February 1864). The first fact is that the USN was disturbed because of existence of the CS submarines (they didn't know how many submarines existed). From the sentence: "The measures for prevention may not be so obvious." it is clear that Rear-Admiral Dahlgren wished to capture the CSN submarine. He ordered non-obvious measures for antisubmarine prevention because he wished to provoke a second attack.

From the CSS Hunley to these days countries with less effective naval power have fought against enemy countries (with superior naval power) by means of submarines, underwater commando forces, fast surface attack ships (torpedo and rocket boats) and so on. The attack on 17 February 1864, made by the CSS Hunley (and sinking of the CSS Hunley and the USS Huasatonic) is significant part of naval history. Unfortunately, the attack took its toll in human lives, on both sides.

Main sources

The USN Naval Historical Center (www.history.navy.mil)Friends of the Hunley, Inc. (www.hunley.org)

This article was published on 30 Oct 2005.