The U-505 Episode

Captain Gallery began to consider the possibility of boarding and capturing a U-boat. In his book "Twenty Million Tons Under the Sea" he relates how, while he was in command of the American airbase at Reykjavik, [Iceland] the officers would sit around in the evenings thinking up ways in which a PBY flying boat might capture a sub. Now this was all in good sport after a few good belts from the bar at the officers club. But the basic idea was as follows: A U-boat has been depth charged and damaged such that it is unable to submerge. The PBY lands astern and taxis up to the sub with the bow gunner beating a tattoo on the conning tower with his machine gun just to let the subs crew know it is not safe to come up on deck. Hooking a wing over the conning tower the PBY locks itself up to the sub and the aircrewmen, carrying a length of chain and some Tommy Guns, jump onto the subs deck, fire a burst or two down the hatch just to discourage any interference, and having made one end fast heave the chain down the ladder so the hatch can't be closed. They then radio for help and locked up on the sub wait for a destroyer to arrive on the scene and take them all aboard.

As wild, funny, and outrageous as this scenario seems, it carried a germ of truth which Gallery carried with him. Might such an idea work? In studying the action reports he had seen several instances in which U-boats had surfaced to give the crews a chance to save themselves. He believed that if prepared, there might have been a chance to get a boarding party on to U-515. It would certainly be a risky venture. The boarding party would have no way of knowing what to expect, even assuming they would be able to get aboard the sub. There could be men aboard ready to fight it out, demolition charges might be set to go off, or the sub itself might be in a sinking condition ready to founder. However, the rewards would be great; code books and encryption gear, communications logs, equipment and the acoustic torpedoes. Talking it over with his commanders they decided to give it a try should the opportunity present itself. The carrier and each of the escorts formed boarding parties and conducted training exercises, in so far as that was possible regarding something which had never been done before. But at least there were a few men on each ship who knew what they would do if an order ever came through the bullhorns which hadn't been heard in the US Navy since 1815 - "Away All Boarders".

At the departure conference in Norfolk held just prior to the start of Guadalcanal's third cruise, Captain Gallery announced his plans to what he describes as a "somewhat skeptical" audience. However, since he received no orders to the contrary he assumed he had a "green" light and proceeded forthwith.

The Third Cruise - May 1944

Actually, the story of the third cruise begins even before Guadalcanal departed Norfolk. (Again a timeline will be used to describe the events which follow):

March/April 1944

In late March, Tenth Fleet's Cdr. Knowles begins analyzing contact reports from what appear to be two submarines which have been detected transiting the Bay of Biscay as they depart on patrol. These two U-boats periodically appear and disappear on the plotting board. Knowles finally decides he is dealing with one submarine, identity unknown. A series of Huff-Duff fixes track the boat down the African Coast to Freetown and then on to Cape Palms. Knowles figures it is one of the older boats with about 90 days duration at sea. He calculates therefore it will turn north for home about the end of May.

15 May - Task Group 22.3 departs Norfolk bound for the Cape Verde Islands on a routine sweep. USS Guadalcanal, Captain D. V. Gallery commanding, with VC-8 aboard, is again accompanied by old friends, the DE's Chatelain, Flaherty, Jenks, Pillsbury, and Pope.

24 May - U-505, the submarine being tracked, although not yet identified, turns north and heads for home in keeping with Knowle's estimate.

27 May - A series of Huff-Duff fixes show Knowles the U-505 is off Bissagos Island about 750 miles north of its last known position off Cape Palms.

28 May - U-505 is fixed by Tenth Fleet off Dakar still sailing north.

30 May - U-505 turns east and heads for the African coast. Tenth Fleet notifies Admiral Ingersoll who passes the information to Guadalcanal with instructions to run down the bearings. The Task Group is now about 300 miles south of the last position fix.

31 May - U-505 moves east close in to the coast off Marsa, turns and heads north again. Guadalcanal is now far astern but closing on a series of fixes provided by Knowles at Tenth Fleet. CIC estimates contact with the sub on 2 June.

2 June - Guadalcanal gets a HF/DF bearing on the sub. Radar contacts are obtained at night. Propeller noises are being heard on sonobuoys. The hunt is heating up. Intense search operations are being conducted continuously by both the surface and air units but a localized contact is not established.

3 June - The Task Group is now at latitude 20 deg. just south of Port Etienne - as analysis later showed, about 150 to 200 miles from U-505. At sunset the Task Group turned back and keeping planes in the air all night re-worked the area just searched with no results. For the past few days the engineering officer, Cdr. Trosino, has been advising the captain the ships fuel supply is becoming dangerously low.

4 June - Sunday morning. The Task Group is off Cape Blanco. Two Wildcats flown by Ensign John W. Cadle and Lieutenant Wolffe W. Roberts are flying close-in ASW patrol. The contact is now estimated to be far astern and with insufficient fuel there is no way to prolong the search. At sunrise Guadalcanal turns north and heads for Casablanca to refuel.

Left: Lt. Wolffe W. Roberts VC-8 - awarded the DFC.

Left: Lt. Wolffe W. Roberts VC-8 - awarded the DFC.

1110 - a radio message is received from Chatelain in her screen position off the starboard quarter; "Frenchy to Bluejay - I have a possible sound contact." - the Task Group has run right over the sub which is now just beneath the surface and between Guadalcanal and the starboard escorts. The order is passed to the screen commander Cdr. Frederick S. Hall riding in Pillsbury to send two of the DE's to assist Chatelain. Guadalcanal turns west to clear the contact area and give the DEs room to maneuver. Pillsbury and Jenks move in to assist. Guadalcanal launches two Avengers with orders not to drop depth charges if the sub surfaces.

Chatelain has evaluated the contact as a submarine and maneuvers to fire a salvo of twenty hedgehogs. After a ten second wait during which no explosions are heard Chatelain circles around again and moves in to fire a depth charge pattern. As she is turning for the attack, U-505 is sighted beneath the surface by the circling Wildcats. The pilots dive firing their guns to mark the spot with bullet splashes.

1121 - Chatelain fires a spread of fourteen six hundred pound depth charges set to explode shallow. The shock waves are clearly felt on the carrier maneuvering just outside the contact area. Chatelain is jolted by her own charges. Aboard U-505 the effect is shattering. A hole is punched in the outer hull, the crew flung about, lights and electrical machinery go off, the rudder jams hard over to starboard, and water begins to enter the boat. Oberleutnant Lange gives the orders to surface. U-505 broached about 700 yds from Chatelain.

The DEs open fire. The Wildcats continue their strafing runs. For a short period U-505 fires back at the attacking aircraft. Oberleutnant Lange was first on to the bridge and is immediately badly wounded by shell splinters. His second officer who had followed him onto the bridge is also wounded and lies unconscious. Lange, looking around him and recognizing he has no chance to escape gives the order to scuttle and abandon ship. Shortly after giving the order he is blown off the anti-aircraft gun deck onto the main deck where some of his men put him over the side in a raft.

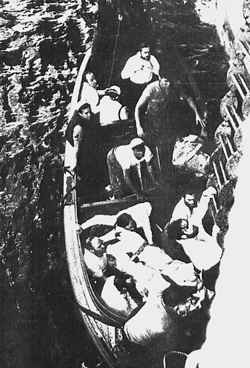

The crew abandon U-505 - men can be seen in the water astern of the sub.

At 1127 when it was seen that U-505's crew was going into the water, the order to cease fire was given. At this time U-505 was circling in a right turn making about 6 knots under power from her electric motors. At 1138 Commander Hall on board USS Pillsbury gave an order not heard in the US Navy for over a hundred years, "Away boarding parties." Lieutenant (jg) Albert L. David was in command of the boarding party from Pillsbury. The small whaleboat could not match the subs speed in a stern chase so the coxwain steered across the circle on a collision course and laid the whaleboat alongside.

Boarding party from USS Pillsbury about to go aboard U-505.

Leaping on to the deck, the boarding party headed for the conning tower. U-505 had now settled deeper in the water and the deck aft of the tower was submerged with the bow up at about a ten degree angle. David followed by Stan Wdowiak RM2/c and Art Knispel TM3/c went down the hatch prepared for a hand-to-hand fight if necessary but found the sub empty; the only light coming from dimly glowing emergency lights. They could hear water gurgling but there was no time to investigate. David called for more of the hands on deck to come down and they set about gathering all the documents they could lay hands on. Knispel and Wdowiak entered the radio room and found the codebooks. Zenon B Lukosius discovered water coming in through a six inch strainer. The cover plate was still on the deckplates beside the sea chest and Luke managed to slap it back in place and dog it down.

U-505 was by this time very near neutral buoyancy. The sea swells were washing over the conning tower hatch and water was pouring in each time a wave passed over. Lieutenant David ordered the men on deck to close the hatch. The motors were still running.

Members of Pillsbury's Boarding Party

While this action was taking place Guadalcanal had put a whaleboat in the water. Commander Earl Trosino, Guadalcanal's engineering officer, arriving on the scene took charge and immediately set about tracing out the boats plumbing and figuring out what had to be done to keep the sub afloat. Gunner Burr went about looking for demolition charges. Intelligence had provided information the U-boats were equipped with 14 five pound demolition charges distributed throughout the boat which could be placed on timers if the boat was to be scuttled. While Trosino was about his work, Gunner Burr found thirteen of the charges and disarmed them. The fourteenth charge was not found until some weeks later after the Task Group arrived in Bermuda; a fact the salvage parties had to endure while working to save the boat during the next few days.

Trosino found if he slowed the boat, lift from the stern planes was lost, the stern went down, and the conning tower hatch went under. Portable pumps were brought aboard and some of the water in the bilges pumped out in an effort to lighten the boat. However, the decision was made to tow the submarine to help keep it afloat until some way could be found to re-establish trim. Pillsbury in attempting to come alongside took the subs bow planes through her side plates which flooded two compartments so she had to back off and commence her own salvage operation.

From left to right: Commander Trosino, Captain Gallery and Lt. Albert David.

From left to right: Commander Trosino, Captain Gallery and Lt. Albert David.

It was decided Guadalcanal would do the tow. The carrier was backed down until U-505's bow was alongside and a 11/4 inch wire made fast. Guadalcanal eased ahead, took up the strain and began towing. As speed was gained, U-505's stern came up and the hatch could be opened again. However, the rudder was still jammed over and U-505 sheared off to the starboard quarter putting immense strain on the towing cable and limiting the towing speed.

The four planes still in the air were now low on gas and had to be recovered. Guadalcanal, towing the reluctant U-505, swung into the wind making about six knots and landed the aircraft. Defensive air patrols were continued over the next several days and more flights were launched and recovered with U-505 dragging along behind.

Just after sunset Flaherty reported a radar contact and Chatelain reported in with a "possible sound contact". The DEs were left to check things out while Guadalcanal with U-505 under tow strained to clear the area. That night the towing cable parted and U-505 floated free. The Task Group spent the night keeping track of the sub which no one expected to see on the surface in the morning. However, U-505 remained barely afloat and a 21/4" cable was bent on. Trosino reported he had been able to get the rudder amidships using the electric controller in the conning tower. But when towing commenced, U-505 sheared off to starboard again. The subs rudder indicator showed amidships but the rudder was still hard over.

Preparing to take U-505 under tow.

It was clear the rudder had to be set amidships and that meant opening the aft torpedo room hatch to get to the manual steering gear. It was not known for sure whether or not the torpedo room was flooded. If it was, there was a risk of losing the boat if the hatch was opened. The hatch was cracked but no water spurted through. So the hatch was opened, the torpedo room entered, and the rudder set amidships. U-505 then towed properly astern. Under Trosino's directions her batteries were charged, and the ballast pumps used to re-establish trim. Guadalcanal proceeded at 8 knots for a rendezvous with the fleet tug Abnaki and the tanker Kennebeck. At one point, Guadalcanal, in a feat of seamanship never before seen in the US Navy, conducted flight operations while simultaneously refueling from a tanker alongside and towing a submarine. On June 9, Abnaki took over the tow, the Task Group formed a screen around the prize, and course was set for Bermuda.  Upon arrival in Bermuda, Cdr. Trosino requested permission to start U-505's diesels and sail her in under her own power. Capt. Gallery decided not to do this. Later, however, he went on record as having regretted this decision as he was sure Trosino could have pulled it off.

Upon arrival in Bermuda, Cdr. Trosino requested permission to start U-505's diesels and sail her in under her own power. Capt. Gallery decided not to do this. Later, however, he went on record as having regretted this decision as he was sure Trosino could have pulled it off.

left: U-505 crew transfer to USS Guadalcanal

Fifty nine of U-505's crew, including the captain, were aboard Guadalcanal. Only one man, Hans Fisher, had died in this operation; Fisher was one of U-505's original commissioning crew. U-505's crew was imprisoned in Bermuda for several weeks. From there they were moved to a camp in Ruston, Louisiana where they remained until the repatriation process began following the end of the war in 1945.

The utmost secrecy surrounding the capture of U-505 was required if full advantage was to be taken of the codes, operational information, and equipment obtained. Captain Gallery had a problem. About 3000 men had witnessed and were fully aware of what had happened. Upon arrival in Bermuda the crews were assembled and the facts laid on the line. It was explained why silence was necessary and why no one was to talk about what he had seen or what had happened. All souvenirs were to be turned in.

USS Guadalcanal conducting flight operations with U-505 under tow.

Did no one talk? That will never be known for sure, but what is known is that the Germans as well as the American public, never learned of the capture of U-505 until the war was over. The Zaunkoenig torpedoes carried by U-505 were turned over to the Harvard Underwater Sound Lab for study. The code books and cipher machines were used to aid in reading the operational traffic between U-boat Headquarters and the U-boats at sea.

Statement of Commanding Officer of U-505

USS GUADALCANAL at sea, June 15, 1944

On June 4th about 1200 I was moving underwater on my general course when noise bearings were reported. I tried to move to the surface to get a look with the periscope. The sea was slightly rough and the boat was hard to keep on periscope depth. I saw one destroyer through West, another through Southwest and a third at 160 degrees. In about 140 degrees I saw far off, a mass that might belong to a carrier. Destroyer #1 (West) was nearest to me, at about 1/2 mile. Further off I saw an airplane, but I had no chance to look after this again because I did not want my periscope seen. I dove again and quickly, with noise, because I could not keep the boat on periscope depth safely. I suppose that the airplane must have seen me because if these heavy boats are rolling under the surface they make a large wake.

I had not yet reached the safety depth when I received two bombs at a distance and then close after them two heavy dashes, from depth charges perhaps. Water broke in; light and all electrical machinery went off and the rudders jammed. Not knowing exactly the whole damage or why they continued bombing me, I gave the order to bring the boat to the surface by pressed air.

When the boat surfaced, I was first on the bridge and saw now four destroyers around me, shooting at my boat with .50 caliber and anti-aircraft. The nearest one, in now by 110 degrees, was shooting with shrapnel into the conning tower. I got wounded by numerous shots and shrapnel's in both knees and legs and fell down. At once I gave the order to leave the boat and to sink her. My chief officer, who came after me onto the bridge, lay on the starboard side with blood streaming over his face. Then I gave a course order to starboard in order to make the aft part of the conning tower lee at the destroyer to get my crew out of the boat safely. I lost consciousness for I don't know how long, but when I awoke again a lot of my men were on the deck and I made an effort to raise myself and haul myself aft. The explosion of a shell blew me from the first antiaircraft deck down into the main deck; the explosion hit near the starboard machine gun.

I saw a lot of my men running on the main deck, getting pipe boats clear. In a conscious moment, I gave notice to the chief that I was still on the main deck. How I got over the side I do not know exactly, but I suppose by another explosion. Despite my injuries I somehow managed to keep afloat until two members of my group brought me a pipe boat and hoisted me into it; my lifejacket had been punctured with shrapnel and was no good. During all this time I could not see much because in the first seconds of the fight I had been hit in the face and eye with splinters of wood blasted from the deck; my right eyelid was pierced with a splinter.

When I sat in the pipeboat I could see my boat for the last time. Some of my men were still aboard her, throwing more pipe boats into the water. I ordered the men around me to give three cheers for our sinking boat.

After this a destroyer picked me up where I received first aid treatment. Later, on this day, I was transferred to the carrier hospital and here the Captain has told me that they captured my boat and prevented it from sinking.

Harald Lange

Oberleutnant z. See d, Res.

Implausible as it all seems now, what started as an entertaining game at the officers club in Reykjavik, ended in Chicago where U-505 rests today at the Museum of Science and Industry as a monument to those who died in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Departing Bermuda on June 20, the Task Group entered Hampton Roads on June 22 and moored back home at the Naval Operating Base, Norfolk.

The Final Patrols

USS Guadalcanal's career as a sub-hunter was almost over. Two more ASW patrols were made in August and October 1944 without encountering any submarines. By this time U-boat activity in the central Atlantic was almost non-existent, except for a brief flare-up in the spring of 1945 just before the end of the war with Germany. Most of the Casablanca-class carriers at this time were being assigned to other duties.

In September 1944 Captain Gallery was relieved by Captain B. C. McCaffree. The October cruise encountered an Atlantic storm with winds to 60 knots and waves estimated at 55 feet high. Guadalcanal sustained severe damage and upon return to Norfolk on 6 Nov. was dry docked for repairs.

Duty as a Training Ship

Re-assigned as a training ship, Guadalcanal departed Norfolk on 1 Dec. 1944 for Bermuda to conduct ASW training exercises. The year 1945 was spent qualifying carrier pilots out of the air stations at Jacksonville and Pensacola, Florida interspersed with two cruises in the spring of 1945 to the Naval Base, Guantanama Bay, Cuba to train for the invasion of Japan. After Japan's surrender in Aug 45 carrier air-qualification duty continued on into 1946.

USS Guadalcanal conducted her last flight operations on 9 February 1946. The deck log for that day contains the following entry; "Increased speed to 16 knots, 146 RPM. 1017 - Launched five F4Us to return to NAS, Norfolk, Virginia. Secured from carrier qualification landings having made 64 landings and qualified 11 pilots. Set base course 303T, increased speed to 17 knots, 157 RPM."

On 5 April 1946, Guadalcanal was towed into the de-commissioning yards and moored at Convoy Escort Pier #22 in Norfolk. Here she found herself in the company of her sister ships in the Battle of the Atlantic, Mission Bay CVE-59, Tripoli CVE-64, Card CVE-11, and Croatan CVE-25. At 1015 on 15 July 1946 the commissioning pennant was hauled down and USS Guadalcanal sailed off into the history books, having been awarded the Presidential Unit Citation and two battle stars for her work in the Atlantic.

Epilogue

1959 Associated Press wire dispatch:

Honolulu, Dec. 16 - (A.P.):

Two obsolete aircraft carriers and a Dutch tugboat were tossed helplessly today in a Pacific storm south of Midway Island. Four ships sped to their rescue. High seas broke towlines from the tug Elbe to the two small United States carriers, Guadalcanal and Mission Bay. Then one of the broken tow lines fouled in the Elbe's propeller and she, too, was helpless. The Navy said the Elbe carried a crew of 25 and a crew of eight men was on each of the carriers. The carriers were being towed to Japan for scrapping.

USS Guadalcanal

- Chapter 1 - Commissioning USS Guadalcanal

- Chapter 2 - Training for battle

- Chapter 3 - The First ASW Cruise

- Chapter 4 - Night Flying Initialized

- Chapter 5 - The U-505 Episode