October 1914 - The Dawn of the U-boat Menace

by James Hinton

It is late October, 1914. World War I has been going on for three months. In London the Admiralty is in a state of shock, still attempting to come to grips with events that had occurred during the previous month and a half. The world's most powerful navy had suffered staggering losses to the Imperial German Navy, and they had lost them to cheap, crude tin cans not fit for human habitation.

German submarine SM U 21, under the command of Kapitänleutnant Otto Hersing, had sunk the cruiser H.M.S. Pathfinder with a single torpedo on the 5th of September, killing 250 of the 268 men believed to be aboard. 2 and half weeks later the SM U 9, skippered by Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen Topped U 21 by sinking three cruisers, the HMS Aboukir, HMS Hogue, and HMS Cressy, in less than an hour, killing 1,459 British sailors. Not content with this, the same "pig boat" turned around and sank the unlucky cruiser H.M.S. Hawke on the 15th of October with a loss of 524 lives.

The Admiralty had scrambled to keep the public from knowing the scope of the disaster. However, with five cruisers sunk and 2,233 dead sailors there was a lot of covering up to do. Worse, Pathfinder had been sunk close enough to the shores of the Isle of May for the entire incident to have been witnessed by no less than Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World, as well as Scottish fishermen. Word got out, fast. The Admiralty was not only on the defensive at sea, it was on the defensive in the press and in Parliament. And unfortunately, it had no response immediately to hand.

What they didn't know was that things were about to get worse. Much worse. Events on the 20th and 26th were about to display that the sinkings of these five cruisers were, in fact, the least of England's concerns. If those five ships represented a blow to Britain's face, the U 17 was about to hit below the belt.

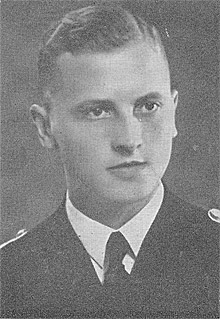

It is the 20th of October and the SS Glitra is sailing past Skudenes on the southern tip of Norway. Her destination is Stavenger, Norway, approximately 30 nautical miles away, and her crew is preparing for their arrival in port. She would never arrive. Instead she would be hailed by the slender and ominous U 17, under the command of Oberleutnant zur See Johannes Feldkirchener.

An old ship, Glitra couldn't have run if she tried. She was thirty years old and could only make 9 knots, leaving her hours from safety. U 17 was faster than that submerged. On the surface she could have run circles around the 866 ton steamer. The only other vessel in the area was a Norwegian torpedo boat, and Norway was strictly neutral. There would be no intervention there. Glitra had no choice. She drifted to a stop and waited to be boarded.

Feldkirchener wasted no time. A prize crew was placed aboard in accordance with international law regarding the merchant fleets of belligerents. Unfortunately for the Glitra, a prediction made two years earlier by retired First Sea Lord Sir John Fisher proved to be prescient. With a crew of only 4 officers and 25 men, U 17 had no one to spare to sail their prize to Germany. Just as Sir John had predicted would be the case, Feldkirchener ordered the British civilians to take to the lifeboats, then scuttled the Glitra.

Sir John had been a Cassandra-like figure about more than just the scuttling. He had first gone to sea in the Royal Navy before the Hunley attacked the Housatonic. His modernization efforts as First Sea Lord had seen the creation of the first all big gun battleships, battlecruisers, torpedo boats, destroyers, oil driven engines, and the implementation of torpedoes as a British tool of war. He had savagely slashed obsolete warships from the Navy, modernized construction methods, and slashed the budget, resulting in a more powerful navy that cost less to operate.

From the point Greece had purchased the Nordenfelt I Sir John had been watching submarines like a hawk. In 1912 he delivered a report to the British cabinet clearly predicting that submarines would become one of the chief weapons of naval warfare in the 20th century. Further, and more dangerously, he predicted that the difficulties faced by submarines when it came to complying with the rules of prize warfare would mean that they would quickly come to ignore them altogether. Agreements that same year were leading to the arming of some merchant ships as "auxiliary cruisers" for their protection. With no realistic chance of capturing armed merchantmen, and no chance of getting captures safely home even if they could, he predicted that submarines would soon drop compliance with prize laws in favor of survival.

The First Lord of the Admiralty rejected the report. Neither he, nor senior naval advisors who had served under and alongside of Sir John could conceive of such a notion. The warning was dismissed as being unnecessary as unrestricted submarine warfare was something no civilized nation would ever consider.

The First Lord of the Admiralty? Winston Churchill.

The Glitra wouldn't be at the bottom for a week before Sir John's more dire prediction would be proved to be horribly, terribly right, and Winston Churchill's advisors wrong. Under the command of Rudolf Schneider, U 24 would introduce the world to what unrestricted submarine warfare would look like on October 26th. While the loss of life would be paltry compared to what had happened to the five British cruisers previously sunk, the potential that could have been lost was nothing less than terrifying.

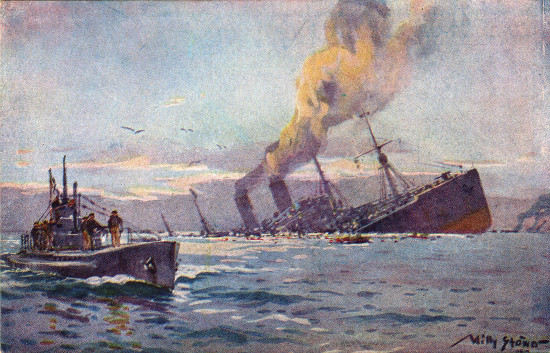

The French ferry Admiral Ganteaume was sailing alongside of British ferry SS Queen that day. Both vessels were engaged in bringing refugees from Belgium to the safety of Havre, France. Both were loaded to the rafters with people, the Ganteaume carrying at least 2,000 souls alone. Seas were a bit rough that day as both ships were approaching the coast of Kent.

Without any warning whatsoever, Schneider slammed one of U 24s torpedoes directly into Ganteaume's side. A gout of water shot into the air alongside of the stricken ship. Amongst the refugees there was immediately a panic. Several people leaped overboard into the water, but the heavy seas would immediately tow them under never to resurface. An attempt was made to lower a life boat, but this, too, failed, and all aboard lost.

The SS Queen immediately made an effort to come to the rescue. Her captain brought her alongside in an effort to transfer passengers to the safety of the British vessel, but the tossing sees made this nearly as hazardous as remaining on the Ganteaume. One witness aboard the Queen gave the following description:

"As soon as we got close alongside her there was an immediate rush for the Queen. The sea was rather high, and the boats heaved to and fro and it was impossible to run a bridge across. The passengers from the Ganteaume had simply to jump from one boat to the other. Some of them missed their footing or failed to hold the taffrail and they either dropped into the water or were crushed between the boats."

In the end the transfer was successfully made. Of the more than 2,000 people aboard Ganteaume only 40 are believed to have been lost. For them, the worst had been avoided. They were brought to Folkestone, England and put ashore, their ordeal over.

For the Admiralty it would only be beginning. Initially convinced that the incident had been the unfortunate result of an errant mine, an inspection would reveal the tell-tale bits of an exploded torpedo in Ganteaume's wreck. The press would publish the accounts of the attack on the French vessel, along with the Admiralty conclusion, to a shocked public. Meanwhile, the Admiralty remained mute on the submarine threat.

In Germany the two incidents would be dealt with very differently. While no one had anything negative to say about Feldkirchener and the Glitra, Schneider's attack had been alarming to many. His attack was hotly debated behind closed doors, with a great deal of concern about a potential backlash from neutral nations such as the United States. No less a personage than the German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg would weigh in, speaking out against any further such attacks taking place. Alfred von Tirpitz was convinced, however, that Feldkirchener's attack was the precursor to necessity, and in February Germany would proclaim a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare that would become the hallmark of the new weapon's deployment in the 20th century.

Efforts to combat the submarine specifically were slow to develop. Even with the Lusitania sinking in May, 1915 being the disaster that Ganteaume barely avoided becoming, it wasn't until 1916 that surface vessels had a realistic means to attack a submerged vessel. Prior to that sinking submarines was only possible as a result of surface actions that led to a gun duel or a ramming. While these did happen it was not a realistic strategy. Only by collecting merchant ships into convoys were the British able to convince German U-boats to deliberately put themselves in a position to be gunned down or rammed. It would take until 1917 for anti-submarine warfare to become an offensive, rather than defensive tool.

In the wake of the war, nations would scramble to deal with this frightening weapon through political restrictions regarding its use. One example would be the 1936 London Protocol. According to Norwich University professor James Kraska the Protocol "prohibited destruction of enemy merchant vessels unless the passengers and crew were first disembarked and their safety assured." He went on to describe how effective these political maneuvers were. "During World War II, however, both the Axis and the Allies routinely disregarded this rule and intentionally targeted the merchant ships of the enemy, in campaigns of unrestricted submarine warfare."

During the 20th century, submarines would prove to be highly dangerous foes. German submarine attacks during WWI would accumulate a total of nearly 13M tons, accounting for almost 5,000 ships and 15,000 lives. Their own losses would be a "mere" 217 vessels and 5,000 lives. In WWII the U-boat would add nearly 3,000 more ships and 14.5M tons. The U.S. Navy, having learned from the German example, would be responsible for adding another 4.9M tons of merchant sinkings caused by submarine, and completely eradicated the Japanese merchant fleet.

The most telling comment regarding the effectiveness of the method of war kicked off in October 1914 would be made by Winston Churchill. The man who had ignored the warnings of Sir John Fisher in 1912 would oversee two world wars that destroyed more than 30M tons of merchant shipping with submarines. After those wars ended he reflected his new understanding of submarines with one simple phrase. "The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril."

James Hinton is the son of a navy family. He has a fondness for history education that leaves his four daughters constantly rolling their eyes at the dinner table.

This article was published on 11 Oct 2014.