Fighting the U-boats

Aircraft & Air ForcesAmerican Air Forces

The Battle against the U-boat in the American Theater

December 7, 1941 - September 2, 1945The political settlement ending World War I left a bitter legacy that poisoned international relations and led within 20 years to an even more devastating war. By the 1930's, totalitarian regimes in central Europe and Japan threatened their neighbors. In the Far East, Japan occupied Manchuria in 1931 and 1932, a first step in seeking the domination of China over the next dozen years. In Europe, Adolf Hitler assumed dictatorial power in Germany in 1933 and rebuilt that country's military forces. Between March 1938 and September 1939, Hitler annexed Austria, dismembered Czechoslovakia, and, with the acquiescence of the Soviet Union, invaded Poland on 1 September 1939. Having guaranteed the integrity of Poland's borders, Great Britain and France declared war against Germany on 3 September. Between February and June 1940, Germany overran Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France, leaving only Great Britain to oppose Hitler's ambitions in western Europe.

As the world edged closer to another major conflict, the United States maintained a strong isolationist position in the international community. By 1939, however, President Franklin D. Roosevelt realized that the United States could not remain neutral indefinitely as the Axis Powers-Germany, Italy, and Japan gradually escalated their aggression and violence. While the United States remained unwilling to wage war, President Roosevelt gave China in the Far East and Great Britain in Europe all the encouragement and support possible.

While providing aid to China and Great Britain, the United States began to build its war industry and rearm, thus preparing for entry into the war. President Roosevelt sought to make the United States an "arsenal for democracy." The Allies obtained armaments and supplies from United States manufacturers, at first on a "cash and carry" basis, later on credit under the Lend-Lease program.

By 1941, the German submarine offensive against Allied shipping in the Atlantic threatened to starve Great Britain. Like Japan, she was dependent on ocean borne commerce to sustain her economy and defend herself. The British population depended on imports for a third of its food and for oil from North America and Venezuela to sustain its lifeblood, but German submarines in 1940 and 1941 were sinking merchant ships and tankers faster than the British could replace them. Consequently, the United States gradually undertook a greater role in the campaign that British Prime Minister Winston Churchill named the Battle of the Atlantic.

In September 1941, the U.S. Navy began to escort convoys in the western part of the North Atlantic. Within a month, a German submarine attacked a U.S. destroyer (USS Kearney, DD432 on 17 October 1941) escorting a convoy near Iceland, leaving several sailors dead or wounded. On 31 October, a German submarine [U-552 under Topp] sank a U.S. destroyer (USS Reuben James, DD245) 600 miles (966 km) west of Ireland, killing 115 of the crew.

The Flush deck destroyer USS Reuben Jones

Despite this loss of life, events in the Far East rather than in Europe pushed the United States into World War II. By July 1941, Japanese forces had occupied French Indochina, and U.S. economic sanctions had cut off much of Japan's oil and other imported resources. In October, the Japanese government decided on war, even as it negotiated with the United States. Japanese military leaders hoped to strike a blow that would paralyze the U.S. fleet in Hawaii long enough to establish a defensive ring from Southeast Asia through the East Indies and eastward in the Pacific as far as Wake Island. This strategic plan would have provided Japan with unlimited access to the rich resources of Southeast Asia. As the opening stage of this plan, a Japanese aircraft carrier task force attacked the American naval base at Pearl Harbor and nearby facilities in Hawaii on 7 December 1941.

THE ROLE OF THE US ARMY AIR FORCES IN THE ANTI SUBMARINE CAMPAIGN

The United States was not prepared for war. Though the Battle of the Atlantic had raged since September 1939, the United States lacked ships, aircraft, equipment, trained personnel, and a master plan to counter any serious submarine offensive. However, steps taken just before and shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack helped the U.S. Navy enhance its submarine defenses. The U.S. Coast Guard was transferred to the U.S. Navy in November 1941, and the next month President Roosevelt named Admiral Ernest J. King Commander in Chief, United States Fleet. In March 1942, the admiral became Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) as well, giving him the authority and means to direct the U.S. effort in the Battle of the Atlantic, particularly in the American Theater.

This theater included the North and South American continents, except Alaska and Greenland, and the waters about the continents to mid Atlantic and mid Pacific Oceans. After Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy organized its existing East Coast naval districts into sea frontiers, with the Eastern Sea Frontier extending from the Canadian border to northern Florida. The Gulf Sea Frontier encompassed the Gulf of Mexico as far south as the border between Mexico and Guatemala, most of the Florida Coast, the northern half of the Bahamas, and the eastern half of Cuba. The Panama Sea Frontier covered the Pacific and Atlantic coasts of Central America and Colombia, and the Caribbean Sea Frontier included the rest of the Caribbean and the northeast coast of South America.

To provide adequate anti submarine measures in this vast area, the U.S. Navy needed trained manpower and specialized surface vessels. As early as 1937, it started training personnel for convoy escort duty in surface vessels, but by 1941 had only a few qualified officers for this duty. Shortly before the United States entered the war, the U.S. Navy's General Board chose the Hamilton Class Coast Guard Cutter as the ideal anti submarine ship. It proved to be an outstanding American escort vessel, but as late as October 1942 only five were on anti submarine convoy patrol in the North Atlantic. The U.S. Navy also had too few destroyers for its needs, even with the use of World War I era ships, and for the first few months of the war had to rely on smaller craft, including civilian yachts, for anti submarine patrols.

The U.S. Navy's air arm in 1941-1942 was as inadequate as its anti submarine surface fleet. Initially, the U.S. Navy had no escort carrier, a type that eventually was very effective against the German submarines. It also lacked aircraft capable of long range [radius of 400600 miles (644966 km)] or very long range [radius up to 1,000 miles (1,609 km)] patrols over the ocean.

Prewar plans called for the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) to support naval forces in case of an emergency. To supplement its meager anti submarine forces, the U.S. Navy turned to the USAAF, commanded by General Henry ("Hap") H. Arnold. USAAF doctrine, however, emphasized strategic bombing, and the USAAF had no equipment or trained personnel for the specialized job of patrolling against, detecting, and attacking submarines from the air.

The USAAF's medium and long range bombers, including the twin engine Douglas B-18 Bolos and North American B-25 Mitchells and the four engine Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and Consolidated Vultee B-24 Liberators, were potentially capable of an anti submarine role. These carried bombs rather than depth charges and lacked radar or other special submarine detection equipment. Also, like the U.S. Navy, the USAAF had many demands for the few aircraft on hand. The shortage of aircraft equipped for anti submarine war continued into mid 1943, with fighters and light bombers often used as anti submarine aircraft.

A B-17 bomber

Initially, the USAAF leadership considered the USAAF's role in anti submarine war to be temporary, and the major thrust of its efforts remained strategic bombing. Thus the USAAF somewhat reluctantly began flying anti submarine missions in a two front naval war waged off both the East and West Coasts of the United States.

OPERATIONS OFF THE U.S. WEST COAST

DECEMBER 1941 - FEBRUARY 1943After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the greatest danger of submarine attack apparently was along the West Coast of the United States, but the Japanese submarine fleet never presented much of a threat. Japanese strategic policy limited submarines primarily to attacks on enemy naval forces, with merchant shipping being a purely secondary target. Even if naval policy had been different, in December 1941 Japan had only 20 submarines capable of traveling from Japan to the West Coast.

During December nine of these patrolled off the West Coast, attacking ten commercial vessels and sinking one merchant ship and three tankers. Then, between February and October 1942, four other Japanese submarines patrolled off the West Coast up to a month at a time. They sank seven ships, including a submarine (USS Grunion, SS-216, sunk off Kiska, Aleutian Islands on 30 July 1942), and on at least three occasions attacked installations ashore, inflicting little damage. No Japanese submarines operated off the West Coast again until late 1944, when one sank two more ships.

On 28 November 1941, HQ USAAF ordered the 2nd and 4th Air Forces, the two organizations that shared responsibility for West Coast air training and defense, to support the U.S. Navy in patrolling against submarines. Their commanders worked closely with U.S. Navy authorities to institute offshore patrols that avoided duplication of effort and still covered essential areas of coastal waters.

Lack of experience and different administrative and operational methods initially clouded liaison between the USAAF and the U.S. Navy. The establishment of a joint information center in late December 1941 at San Francisco, California helped solve the liaison problems. Differing methods of patrol created some inter-service tension. The U.S. Navy used a search pattern shaped like a fan, with every aircraft branching out from a central point on diverging courses, while the USAAF flew a parallel track search pattern, with each aircraft on patrol flying parallel within sight of the aircraft on either side. The USAAF pilots soon adopted the fan pattern in the interest of inter-service cooperation and more efficient coverage of the patrol areas. The U.S. Navy flew patrols close to the shore, but the USAAF anti submarine missions ranged up to 600 miles (966 km) offshore from Seattle, Washington, in the north all the way south to the coastline of Lower (Baja) California.

In December 1941, the USAAF had only 45 modem fighter aircraft, 35 medium bombers and ten long range bombers stationed on the West Coast. To meet the immediate need for more long range aircraft, on 8 December, the USAAF created a temporary collection agency of air crews and B-17's formerly bound for the Philippine Islands. This "Sierra Bombardment Group" participated in offshore patrols until early January 1942 when the absence of an immediate threat became obvious and scheduled movements of aircraft to the Southwest Pacific could resume.

While the Sierra Bombardment Group provided short term relief from personnel and aircraft shortages, it did not solve problems presented by untrained, inexperienced personnel and lack of submarine detection equipment. The available aircraft were not equipped with radar or other devices, and detection of enemy submarines depended solely on eyesight. The anti submarine air crews occasionally mistook whales and floating logs for Japanese submarines. They frequently reported and attacked enemy submarines, but rarely confirmed results. A B-25 crew of the 17th Bombardment Group (Medium), 2d Air Force, bombed a submarine near the mouth of the Columbia River on 24 December 1941. They claimed it sank, but in fact no Japanese submarine was sunk off the West Coast during World War II.

In February 1943, the USAAF ceased flying anti submarine patrols off the West Coast. Japanese submarines had not appeared off the coast since October 1942, and U.S. Navy aircraft and surface vessel strength had grown sufficiently strong to handle any new threats.

OPERATIONS OFF THE U.S. EAST COAST

DECEMBER 1941 - JUNE 1942In complete contrast to the West Coast, German submarine forces posed a deadly threat to U.S., British, Canadian, and other Allied shipping off the East Coast of the United States. Because of British reliance on imports, Germany's leaders sought to destroy Allied shipping. Admiral Karl Doenitz, commander of Germany's submarine force, had formulated a strategy of attacking Allied shipping at weakly defended points to achieve the greatest destruction at the least cost. Furthermore, Germany had the submarine force to pursue Admiral Doenitz's strategy. It began 1942 with 91 operational submarines; at the peak of its strength a year later, it had 212. These submarines, sailing from bases in France, took about three weeks to reach American waters. Modified to carry an extra 20 tons of fuel, they could remain on patrol two to three weeks, and averaged 41 days at sea. Admiral Doenitz managed to extend this time by refueling and resupplying the operational submarines from specially modified submarines. Called "milch cows," they carried enough fuel and supplies to resupply other boats and extend their time at sea to an average of 62 days with one refueling and 81 days with a second refueling. The first submarine "milch cow" deployed at sea in March 1942.

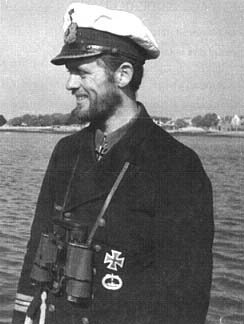

The sudden entry of the United States into World War II caught Admiral Doenitz by surprise, with no submarines immediately available to send to American waters. He allocated five long distance submarines, all he could quickly make ready, to Operation DRUMBEAT, his code name for operations against shipping in U.S. coastal sea lanes. These sailed from Lorient, France, between 23 and 27 December 1941. On 11 January 1942, some 300 miles (483 km) east of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, the leading submarine, U-123, commanded by Captain Reinhard Hardegen, sank an Allied merchant ship, the first combat loss in the American Theater. Three days later, Captain Hardegen sank another ship just off the coast of Massachusetts.

Kptlt. Reinhard Hardegen |

Using these tactics, the Germans between mid January 1942 and the end of June sank 171 ships off the East Coast, many of them tankers. For several months, the German submarine offensive gravely threatened the cargo carrying capability of the Allies. Not until the last quarter of 1942 did the United States build merchant ships rapidly enough to offset losses inflicted by the German submariners. During the first half of 1942, the Allies lost three million tons of shipping, mostly in American waters. The submarine attacks claimed about 5,000 lives, and the loss of irreplaceable cargoes grievously endangered Great Britain's ability to continue the war.

This perilous situation resulted in part from the tragic U.S. delay in taking such precautionary measures as controlling maritime traffic and organizing submarine defenses. German submarine captains arriving in American waters in the first half of 1942 found merchant ships following peacetime sea lanes and sailing practices. The ships, sailing independently instead of in convoys, were silhouetted at night against the brightly lit coast, making the job of the enemy much easier. U.S. military leaders until May 1942 undertook little effective action to find and attack submarines whose positions were known through distress signals from torpedoed ships or to redirect merchant shipping away from waters where attacks had taken place. While no one reason can be cited for the delay in instituting defensive measures, the general state of American unpreparedness is perhaps the best explanation.

Early in the war the USAAF and the U.S. Navy pooled their meager resources for anti submarine patrols. In response to a U.S. Navy request, the USAAF on 8 December 1941, directed the I Air Support Command and I Bomber Command of the 1st Air Force to initiate patrols in the Eastern Sea Frontier. The I Air Support Command's observation and pursuit (fighter) aircraft patrolled out to 40 miles (64 km) offshore from Portland, Maine, south to Wilmington, North Carolina, but usually had fewer than ten aircraft per day on patrol. The I Bomber Command, 1st Air Force, relied on its medium B-25 and B-18 bombers to fly up to 300 miles (483 km) offshore and its heavy B-17's to cover up to 600 miles (966 km) out. On the average, however, until March 1942 this command had only three aircraft flying each day from Westover Field, Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts, and three from Mitchel Field, Hempstead, Long Island, New York, not nearly enough to patrol the Eastern Sea Frontier effectively.

The USAAF obtained the assistance of the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) to augment I Bomber Command's efforts. Organized a week before the war began, the CAP consisted of civilian pilots willing to fly their own aircraft off the coast to look for submarines and to assist in the rescue of survivors. Receiving only aviation gasoline from the USAAF, the CAP began patrolling on 8 March 1942, eventually establishing 21 stations from Bar Harbor, Maine, to Brownsville, Texas. With the help of the CAP, the I Bomber Command flew almost 8,000 hours in March, about as much as in January and February combined. The additional patrols forced German submarines to remain submerged except on the darkest nights.

As the number of patrols increased, the USAAF overcame numerous deficiencies in its anti submarine efforts. Originally, aircraft were unarmed or armed with bombs instead of depth charges. They could not fly at night and none had radar before March 1942. The air crews lacked training in navigation, recognition of ships, and anti submarine attack tactics. In December 1941, forced to rely on eyesight alone, they often reported incorrectly the sighting of surfaced and submerged submarines. On 29 December near Newport, Rhode Island, a USAAF bomber dropped four bombs on a U.S. Navy destroyer that the air crew had mistaken for a submarine. Fortunately, the bombs exploded harmlessly.

The United States sought the guidance of Great Britain, which had been waging anti submarine war against Germany since 1939. As suggested by the British, the USAAF and the U.S. Navy established a Joint Control and Information Center in New York City on 31 December 1941. The center tracked the movements of merchant shipping, plotted enemy contacts, and determined the locations of all surface and air anti submarine patrols.

One British capability the Americans remained unable to exploit until mid 1943 was intelligence that virtually pinpointed the locations of enemy submarines. During the inter war period, Germany developed a machine, called Enigma, to encipher the military codes used to transmit radio messages. Early in World War II the British, in cooperation with the French and Polish govemments in exile, developed the means to break the German codes enciphered by the Enigma, with intelligence derived from the broken codes known as ULTRA. The British routed convoys around the locations of enemy submarine wolf packs, using ULTRA information as well as intelligence derived from aerial reconnaissance, radio fingerprinting (identification of individual enemy radiomen by their distinctive method of sending messages), and radio direction finding. Shortly after the United States entered the war, Great Britain agreed to provide pertinent ULTRA intelligence to the U.S. military. However, on 1 February 1942, Germany replaced its original Enigma machines on the Atlantic Uboat net with a new, more complex machine employing more encrypting rotors, resulting in codes that the British could not decipher. Not until 13 December 1942, six weeks after the capture of German code books related to the new Enigma from a badly damaged enemy submarine, were the British able to again read the German Uboat code. (They soon discovered that the Germans had broken the Allied code directing convoy traffic, a discovery that resulted in a new British code in March 1943.) By August, the British and Americans were reading German messages almost as soon as they were intercepted, but for much of the time between January 1942 and October 1943, when the USAAF participated extensively in the anti submarine war, ULTRA intelligence was sporadic or nonexistent.

To add to the intelligence woes of the Americans in 1942, the U.S. Navy initially failed to send the information it did receive from the British to the using commands. Consequently, the intelligence was not being used in operations against the enemy. Even if it were disseminated, intelligence data often lost its usefulness because it was not quickly communicated from U.S. Navy to Army organizations or down the chain of command in either service.

In large part, the intelligence lapse stemmed from the chaos and confusion that Army and U.S. Navy commands suffered in the first few months of the war. This confusion also led to faulty tactics that usually resulted in unsuccessful attacks on enemy submarines. Attacked submarines often escaped because the aerial and surface attacks were sporadic rather than sustained. Through inexperience, poor training, and lack of adequate forces, both U.S. Navy surface forces and USAAF air crews often failed to follow up initial anti submarine attacks.

Once again the USAAF and the U.S. Navy turned to the British for applied lessons in tactics. British tactics exploited the weaknesses of the submarine, which had to surface, usually at night, to recharge its batteries, ventilate the boat, and permit crew members a chance to come topside. Constant aerial patrolling to as far as 600 miles (966 km) out to sea restricted opportunities for submarines to operate on the surface. Until the first USAAF aircraft received radar sets in March 1942, the submarines could surface and attack almost at will during dark nights or inclement weather, but the advent of night flights using radar to locate surfaced submarines added considerably to the value of the routine anti submarine air patrol. By June 1942, I Bomber Command aircraft had vastly increased sightings of and attacks on German submarines.

As the British had learned, when an air crew sighted an enemy submarine, it had to act quickly to achieve surprise. An attack later than 15 to 35 seconds after the submarine submerged usually proved unsuccessful. By flying in clouds and attacking at an angle from 15 to 45 degrees, the pilot increased the chances of a hit or near miss. The attack itself required the aircraft to fly as low as possible, preferably about 50 feet (15 m) above the water, and to drop the depth bomb within 20 feet (6.1 m) of the submarine's pressure hull. As the aircraft passed over the submarine, the air crew would fire the machine guns in an attempt to damage it and suppress antiaircraft fire.

The first successful USAAF aircraft attack on a German submarine, U-701, on 7 July 1942, incorporated these tactics. The official history of I Bomber Command records the attack from an Lockheed A29 Hudson piloted by Lieutenant Harry J. Kane of the 396th Bombardment Squadron (Medium) based at NAS Alameda, California but operating from MCAS Cherry Point, North Carolina.

"Lieutenant Kane attacked by the book. He was flying a routine patrol from Cherry Point, North Carolina. He sighted a submarine seven miles (11 km) away. Since he was using cloud cover, he was able to approach it undetected, closing in on a course of zero degrees relative to the track of the submarine. He attacked from 50 feet (15 m) at 220 miles per hour (354 km/h), releasing three MK XVII depth charges in train about 20 seconds after the target submerged. The submarine was still visible underwater as the bombs fell. The first hit short of the stem; the second, just aft of the conning tower; the third, just forward of the conning tower. Fifteen seconds after the explosions, large quantities of air came to the surface, followed by 17 members of the crew."

Accumulated experience coupled with British coaching, improved radar, depth bombs, and other equipment resulted in noticeably higher levels of success for USAAF anti submarine patrols during July, August, and September 1942. In the previous quarter, only seven of 54 attacks resulted in damage to submarines, but in the third quarter, eight of 24 attacks damaged submarines, not counting the one sunk on 7 July.

By this time, the Americans owed a great deal to the British for sharing their anti submarine experience. But in one area they appeared slow to assimilate British methods. Early in the Battle of the Atlantic, Great Britain had recognized the need for close cooperation between sea and air anti submarine forces at higher as well as operational levels of command. But such cooperation at the higher levels of the USAAF and the U.S. Navy was frequently elusive, partly because of historical rivalry. Between World Wars I and II, the two services had argued bitterly over the roles of their respective air arms, the U.S. Navy insisting on responsibility for all missions over the ocean and the Army insisting on controlling all long range, land based aircraft. The jurisdictional problem continued into the war and at times handicapped efforts to counter enemy submarine attacks in American waters.

Partially as a result of the jurisdictional dispute, multiple headquarters had overlapping responsibility for anti submarine operations. Since its doctrine emphasized centralized operational control of aircraft, the USAAF found this situation objectionable. To achieve centralization, General Arnold in March 1942 proposed to Admiral King the establishment within the USAAF of an organization to conduct all air operations against submarines. The U.S. Navy did not accept this idea because it would give the Army a traditionally U.S. Navy mission and bring naval aircraft under Army control. Most USAAF units involved in anti submarine operations came under I Bomber Command, and, in an effort to reduce organizational confusion, I Bomber Command was placed under the operational control of the Eastern Sea Frontier on 26 March. Gradually, I Bomber Command reoriented the training of its flying personnel, obtained additional aircraft, and adapted its equipment to the anti submarine mission. General Arnold, along with most other USAAF leaders, believed that progress in bringing the USAAF's anti submarine resources and operations under one headquarters was largely offset by U.S. Navy policies. The U.S. Navy allocated the USAAF anti submarine squadrons to the sea sector commanders and would not ordinarily allow aircraft allocated to one sea sector or frontier to operate in another. Transfer of aircraft from one sea frontier to another to meet changing submarine threats proved difficult and usually too late.

This significant difference in U.S. Navy and USAAF doctrine aggravated disputes caused by inter-service rivalry. The USAAF perceived the U.S. Navy command structure as inflexible and its strategic concept as essentially defensive. The U.S. Navy confirmed these perceptions as it built up its forces until it could institute a coastal convoy system, one of the most important and effective defensive measures. The first convoy sailed from Hampton Roads, Virginia, southward bound, on 14 May 1942. Admiral King sought increased support from the USAAF for convoy escort duties. The USAAF preferred to concentrate on long range over water patrols, but until mid1943, the USAAF had to divert considerable aircraft to convoy escort duties, probably the best use of scarce resources.

The formation, equipping, and training of effective sea and air anti submarine forces against the German offensive on the East Coast required time. The U.S. Navy, supported by the USAAF, gradually progressed with various defensive measures and increasingly effective air patrols forced the Germans to greater caution in the waters of the Eastern Sea Frontier. By June 1942, German submariners had turned to the less dangerous waters of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.